Understanding atomic energies is crucial in astronomy because it allows us to decipher the light from stars and other celestial bodies. By analyzing the energies associated with atomic transitions, astronomers can determine the composition, temperature, and other properties of stars.

Video

Watch this video for an explanation of atomic energy levels and emission spectra.

Recap: The Quantum Nature of Light

Remember from our previous lesson that light behaves as both a particle and a wave. This dual nature is fundamental to understanding how light interacts with matter. Photons are the particle aspect of light, and each photon carries a specific amount of energy, determined by its frequency:

\[E = h \cdot f\]

where:

- $E$ is the energy of the photon,

- $h$ is Planck’s constant ($6.63 \times 10^{-34}$ J·s),

- $f$ is the frequency of the photon.

Photons can transfer energy to electrons in atoms, causing the electrons to jump between energy levels. This is the foundation of atomic spectroscopy.

Electron Volts

The energy of photons and electrons is often measured in electron volts (eV), a unit of energy that is more convenient for the small scales involved in atomic physics.

- 1 eV is defined as the energy gained by an electron when it is accelerated through an electric potential difference of 1 volt:

\[1 \, \text{eV} = 1.6 \times 10^{-19} \, \text{J}\]

Example:

Convert 5 eV to joules.Given:

$ 1 \, \text{eV} = 1.6 \times 10^{-19} \, \text{J}$

Solution:

\[5 \, \text{eV} = 5 \times 1.6 \times 10^{-19} \, \text{J} = 8 \times 10^{-19} \, \text{J}\]

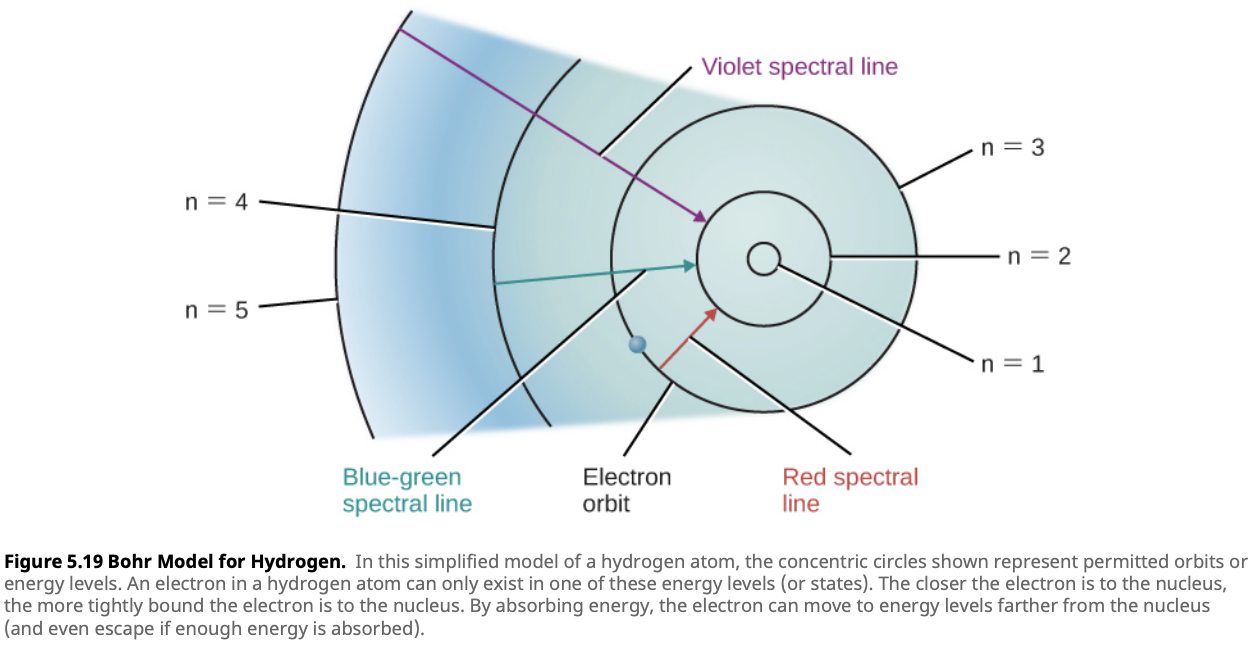

Bohr Model and Atomic Energy Levels

The Bohr model of the atom was a significant advancement in understanding atomic structure. Niels Bohr proposed that electrons orbit the nucleus in specific, quantized energy levels. Electrons can only occupy these discrete orbits and not the space in between.

- Ground State: The lowest energy level an electron can occupy.

- Excited States: Higher energy levels that electrons can jump to when they absorb energy.

These energy levels are quantized, meaning only certain values of energy are allowed. This quantization explains why atoms emit or absorb light at specific wavelengths.

Electron Transitions and Photons

Electrons within an atom are confined to specific energy levels, much like steps on a ladder. They can’t exist between these levels, so to move from one energy level to another, they must either gain or lose energy. This energy comes in the form of photons—packets of light that carry energy.

When an electron absorbs a photon, it gains enough energy to move to a higher energy level—this is known as excitation. Conversely, when the electron falls back to a lower energy level, it releases energy in the form of a photon—a process called de-excitation.

The energy of the photon absorbed or emitted corresponds precisely to the difference between the two energy levels:

\[\Delta E = h \cdot f = \frac{hc}{\lambda}\]

Where:

- $\Delta E$ is the energy difference between the levels,

- $h$ is Planck’s constant ($6.63 \times 10^{-34}$ J·s),

- $f$ is the frequency of the photon,

- $\lambda$ is the wavelength of the photon,

- $c$ is the speed of light ($3 \times 10^8 \, \text{m/s}$).

This relationship is crucial in atomic spectroscopy, the study of how atoms absorb and emit light.

Brief Introduction to Spectra

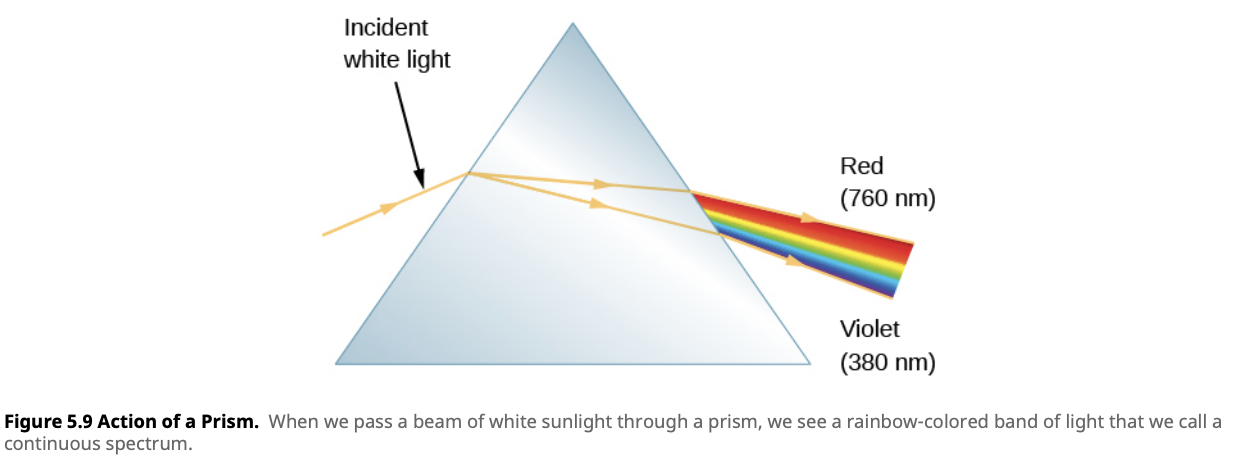

We will be exploring spectra in more detail in the following lessons. For now, let’s start with a simple concept: when white light passes through a prism, it splits into its component colors, creating a continuous spectrum. White light is made up of many different colors, each corresponding to a specific wavelength of light. As the light passes through the prism, it bends by different amounts depending on the wavelength, spreading out into a spectrum that ranges from red to violet.

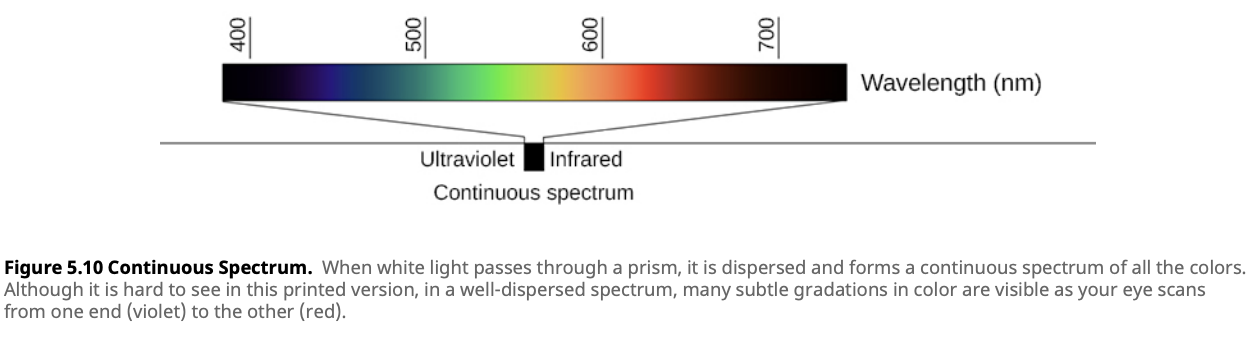

This continuous spectrum is produced by sources of light that emit all wavelengths, such as heated objects like stars. In a continuous spectrum, all visible wavelengths are present, blending smoothly from one color to the next.

An example of a continuous spectrum is shown below. Notice how there are no gaps in the colors—every wavelength of visible light is present. This type of spectrum is typical of objects like the Sun and other stars, where light is emitted across a broad range of wavelengths.

Emission and Absorption Spectra

When electrons move between energy levels, they absorb or emit photons, which gives rise to two other types of spectra:

-

Emission Spectrum: When electrons drop from higher to lower energy levels, they emit photons. These photons appear as bright lines at specific wavelengths, corresponding to the energy difference between the levels. Each element has a unique set of emission lines, similar to a fingerprint.

-

Absorption Spectrum: When electrons absorb photons and jump to higher energy levels, certain wavelengths of light are absorbed from a continuous spectrum. These absorbed wavelengths appear as dark lines in the spectrum, where light is missing. The pattern of these absorption lines is also unique to each element.

Understanding emission and absorption spectra is essential in astronomy, as they allow scientists to determine the composition and properties of stars and other celestial objects by analyzing the light they emit or absorb.

The Hydrogen Atom Spectrum

Hydrogen, the simplest and most abundant atom in the universe, has been pivotal in shaping our understanding of atomic energy levels. With just one proton and one electron, hydrogen serves as an ideal model for exploring how electrons behave within atoms. The spectral lines produced by hydrogen offer a clear demonstration of how energy transitions within atoms correspond to specific wavelengths of light.

Hydrogen’s Spectral Series and Energy-Level Diagrams

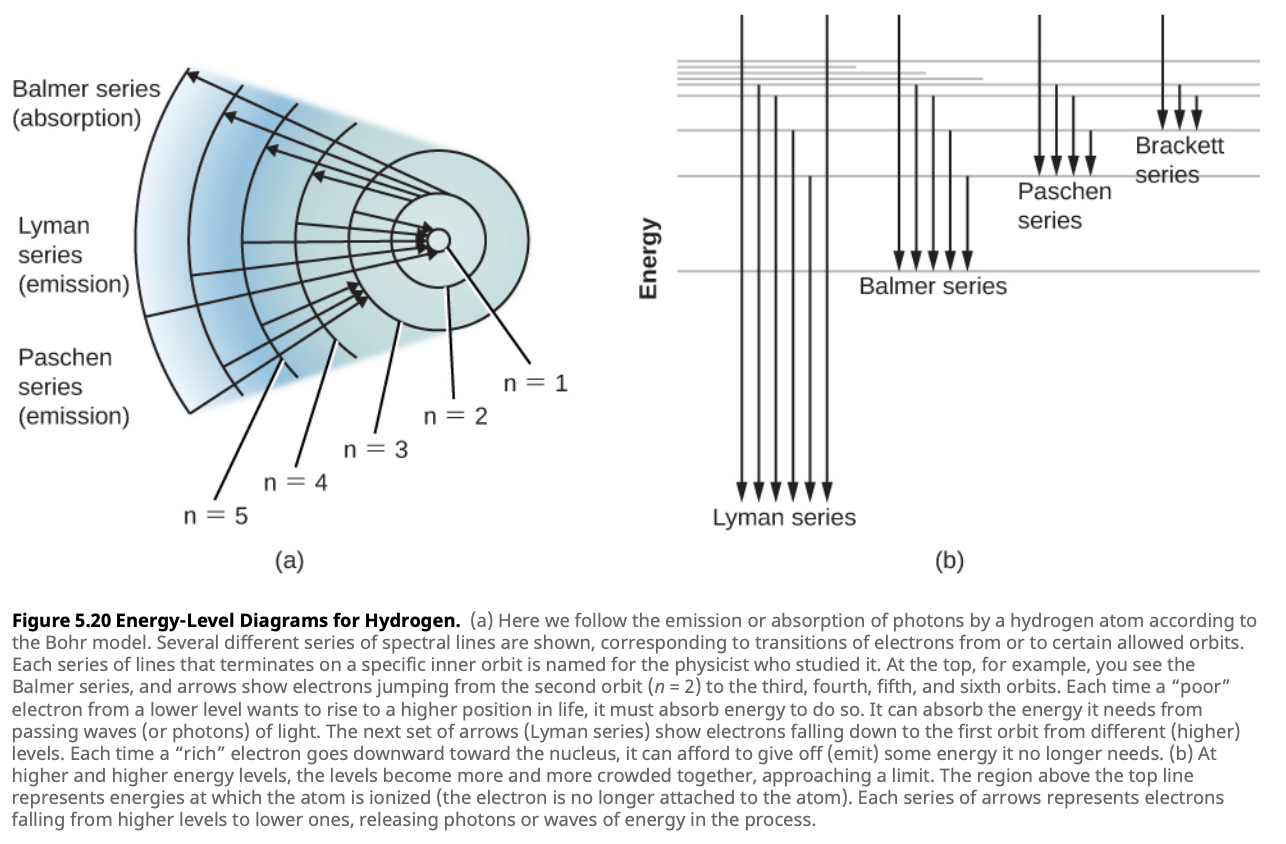

When the electron in a hydrogen atom moves between different energy levels, it either absorbs or emits light. These transitions can be visualized using an energy-level diagram, where each energy level is represented as a horizontal line, and transitions between these levels are depicted as arrows.

The resulting spectral lines from these transitions can be grouped into specific series, each corresponding to the electron’s final energy level. These series cover different regions of the electromagnetic spectrum:

-

Lyman Series: These transitions end at the ground state ($n = 1$). The photons emitted or absorbed in this series fall within the ultraviolet region, making them invisible to the naked eye, but crucial for studying stars and distant galaxies.

-

Balmer Series: This series involves transitions to the second energy level ($n = 2$). The Balmer series is visible in the visible light spectrum and is perhaps the most well-known series, producing distinct colors such as the red H-alpha line and the blue-green H-beta line.

-

Paschen Series: These transitions end at the third energy level ($n = 3$). The resulting spectral lines fall within the infrared region, invisible to the human eye but detectable using infrared telescopes.

Energy Calculations for Atomic Transitions

To calculate the energy of photons associated with atomic transitions, we use the formula:

\[E = \frac{hc}{\lambda}\]

Example:

A photon emitted during the transition from $n = 3$ to $n = 2$ in a hydrogen atom has an energy of 1.89 eV. Calculate the wavelength of light emitted from this transition.We can use the formula:

\[\lambda = \frac{hc}{E}\]Where:

- $h = 6.63 \times 10^{-34} \, \text{J}\cdot {s}$ (Planck’s constant),

- $c = 3 \times 10^8 \, \text{m/s}$ (speed of light),

- $E = 3.02 \times 10^{-19} \, \text{J}$ (energy of the photon).

Substituting the values:

\[\lambda = \frac{6.63 \times 10^{-34} \, \text{J}\cdot {s} \times 3 \times 10^8 \, \text{m/s}}{3.02 \times 10^{-19} \, \text{J}}\]\[\lambda \approx 6.59 \times 10^{-7} \, \text{m} = 659 \, \text{nm}\]This wavelength corresponds to red light in the visible spectrum.

Ionization Energies

Imagine trying to pull a magnet off your fridge. The stronger the magnet, the more effort it takes to pull it away. Similarly, in an atom, the closer and more tightly bound an electron is to the nucleus, the more energy is needed to remove it. This energy is called ionization energy—the energy required to strip an electron completely away from the atom.

Ionization energy plays a critical role in the life of stars. In the searing heat of a star, atoms are constantly bombarded with energy, and when the temperature is high enough, electrons are forcibly removed from atoms. This process of ionization reveals important clues about the physical conditions of celestial bodies.

Ionization Energy for Hydrogen

In hydrogen, the simplest atom, it takes exactly 13.6 eV to remove its single electron and ionize the atom completely. This might not seem like much energy, but in the context of a star, it tells us a lot about the environment in which this atom exists.Applications of Atomic Spectra in Astronomy

Atomic spectra are like a cosmic fingerprint, revealing hidden secrets about the universe. By examining the light from distant stars, astronomers can unlock a treasure trove of information about these celestial objects. Every element in a star emits or absorbs light at specific wavelengths, producing unique spectral lines that act like barcodes. These barcodes allow astronomers to decode the star’s story.

-

Composition: Just as you can identify a song by its melody, astronomers can identify elements in a star by its spectral lines. Each element produces a distinct set of lines, so by analyzing the star’s light, we can figure out what it’s made of—whether it’s hydrogen, helium, or even heavier elements like carbon and iron.

-

Temperature: The intensity of these spectral lines and the ionization states of the elements give us vital clues about the star’s temperature. A hotter star might show more highly ionized atoms, indicating extreme heat in its atmosphere. Spectra help us measure this heat from light-years away!

-

Motion: Stars are constantly in motion, and atomic spectra help us track that movement. Thanks to the Doppler effect, the positions of the spectral lines shift depending on whether the star is moving toward or away from us. This shift allows us to measure the speed and direction of stars as they journey through space.

Understanding atomic energies is at the heart of these astronomical analyses, helping us map out the composition, temperature, and motion of stars across the universe.

Check Your Understanding

-

A photon has a wavelength of $500 \, \text{nm}$. Calculate the energy of this photon in electron volts (eV).

-

Explain how emission lines and absorption lines are formed. In what sorts of cosmic objects would you expect to see each?

-

Explain how electrons use light energy to move among energy levels within an atom.

- Which of the following transitions in a hydrogen atom would produce a photon with the shortest wavelength?

- $n = 3$ to $n = 2$

- $n = 4$ to $n = 2$

- $n = 5$ to $n = 2$

- $n = 6$ to $n = 2$

-

An astronomer observes a star and detects several absorption lines in its spectrum. How can the astronomer use these lines to determine the star’s composition? What information do these absorption lines provide?

-

Calculate the wavelength of light emitted when an electron in a hydrogen atom transitions from $n = 4$ to $n = 2$. Use the given energy for this transition of $2.55 \, \text{eV}$.

-

Explain why ionization energy is important for determining the temperature of a star. What does the ionization state of an element tell us about the conditions within the star?

- A photon has an energy of $2.5 \, \text{eV}$. Calculate its wavelength in nanometers.

Resources

- Astronomy (2016). Andrew Fraknoi, David Morrison, and Sidney C. Wolff.