Since ancient times, humans have looked up at the night sky, captivated by the light from distant stars and planets. Early civilizations used this light to navigate, mark the passage of time, and even develop myths about the heavens. But what exactly is light, and how does it carry information from these distant celestial objects to our eyes and telescopes?

Our journey to understand the nature of light began in the 17th century with thinkers like Isaac Newton and Christiaan Huygens. Newton believed light consisted of tiny particles, while Huygens proposed that it behaved like a wave. These ideas paved the way for later discoveries. In the 19th century, James Clerk Maxwell revolutionized our understanding by developing the theory of classical electromagnetism. He described light as a transverse wave made up of oscillating electric and magnetic fields—an invisible yet powerful force connecting us to the distant reaches of the universe.

Video

Watch this video for an excellent introduction to the concept of light. The video includes a discussion on how light behaves, providing a visual representation of the topics covered in this lesson.

Electromagnetic Waves

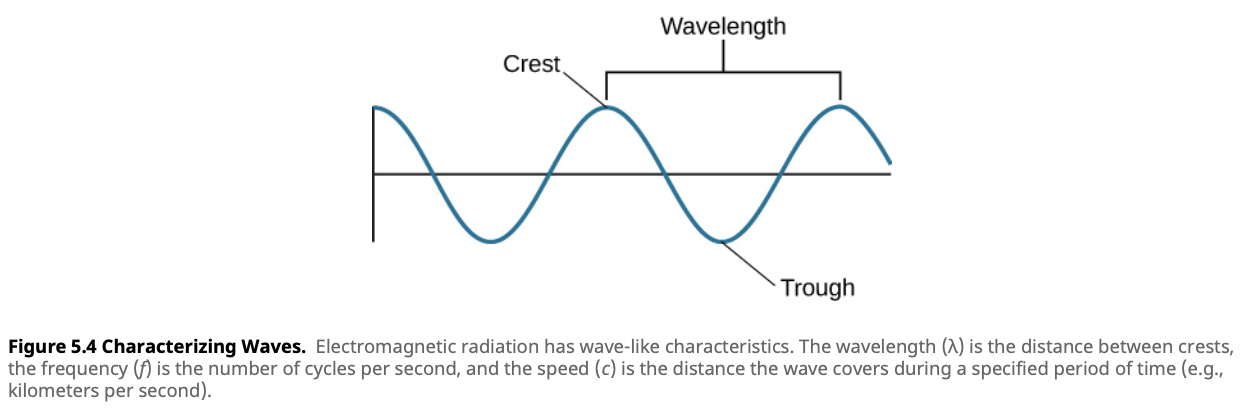

Imagine light as ripples in a pond, where each ripple represents a wave. The amplitude of a wave refers to its height, which determines the brightness of the light. The wavelength is the distance between successive peaks, and the frequency is the number of wave cycles that pass a given point per second. These properties define the behavior of light and help categorize different types of light, from radio waves to gamma rays.

Light waves are unique because, unlike sound or water waves, they do not require a medium like air or water to travel. This ability to travel through the vacuum of space is what allows light to carry information from distant stars and galaxies to Earth, making it crucial for astronomy.

Wave Properties

Light is an electromagnetic wave with key properties such as amplitude, wavelength (λ), and frequency (f). The speed of light in a vacuum is approximately 3 × 108 meters per second (or 300,000 kilometers per second), the fastest known speed in the universe.

Relationship Between Wavelength and Frequency

A fundamental principle in wave physics is that the speed of a wave is the product of its wavelength and frequency. For light, this relationship is expressed by the equation:

\[c = \lambda f\]

where $c$ is the speed of light, $\lambda$ is the wavelength, and $f$ is the frequency. This equation shows that shorter wavelengths correspond to higher frequencies and vice versa.

Units of Frequency

Frequency is a measure of how many wave cycles pass a given point in one second. The standard unit of frequency is the Hertz (Hz), named after the physicist Heinrich Hertz. One Hertz (1 Hz) corresponds to one cycle per second.

For example, a frequency of 1 Hz means that one wave cycle is completed every second. Higher frequencies correspond to more cycles per second:

- 1 kHz (kilohertz) = 1,000 cycles per second

- 1 MHz (megahertz) = 1,000,000 cycles per second

- 1 GHz (gigahertz) = 1,000,000,000 cycles per second

Consider the light from a distant star. Short wavelengths produce blue or violet light (high frequency), while longer wavelengths produce red light (low frequency). This relationship not only explains the colors we see but also helps astronomers identify and classify celestial objects based on the light they emit.

Deriving the Wave Equation

The equation for the relationship between the speed, wavelength, and frequency of a wave can be derived from basic principles of motion. The general formula for average speed is:

\[\text{average speed} = \frac{\text{distance}}{\text{time}}\]For example, a car traveling at 100 km/h covers a distance of 100 km in 1 hour.

Now, let’s apply this concept to an electromagnetic wave. The distance traveled by the wave during one cycle is equal to its wavelength, $\lambda$. The time it takes to complete one cycle is related to the frequency of the wave, $f$. Frequency is defined as the number of cycles per second, so the time for one cycle is $t = \frac{1}{f}$.

For an electromagnetic wave traveling at the speed of light, $c$, the speed can be expressed as:

\[c = \frac{\text{distance}}{\text{time}} = \frac{\lambda}{t}\]Substituting $t = \frac{1}{f}$ into the equation, we get:

\[c = \lambda \times f\]This equation shows that the speed of light is the product of the wavelength and the frequency of the wave. In other words, light waves with shorter wavelengths must have higher frequencies to travel at the constant speed of light.

Example: Using the Wave Equation

Problem: Calculate the wavelength of visible light with a frequency of $5.66 \times 10^{14}$ Hz.

Solution: \(\lambda = \frac{c}{f} = \frac{3.00 \times 10^8 \, \text{m/s}}{5.66 \times 10^{14} \, \text{Hz}} = 5.30 \times 10^{-7} \, \text{m} = 530 \, \text{nm}\)

This wavelength corresponds to yellow-green light in the visible spectrum, which is commonly seen in sunlight.

The colour of light

Remember, the colour of light is determined by its wavelength. This principle is used in spectroscopy to determine what stars are made of by analyzing the light they emit.The Electromagnetic Spectrum

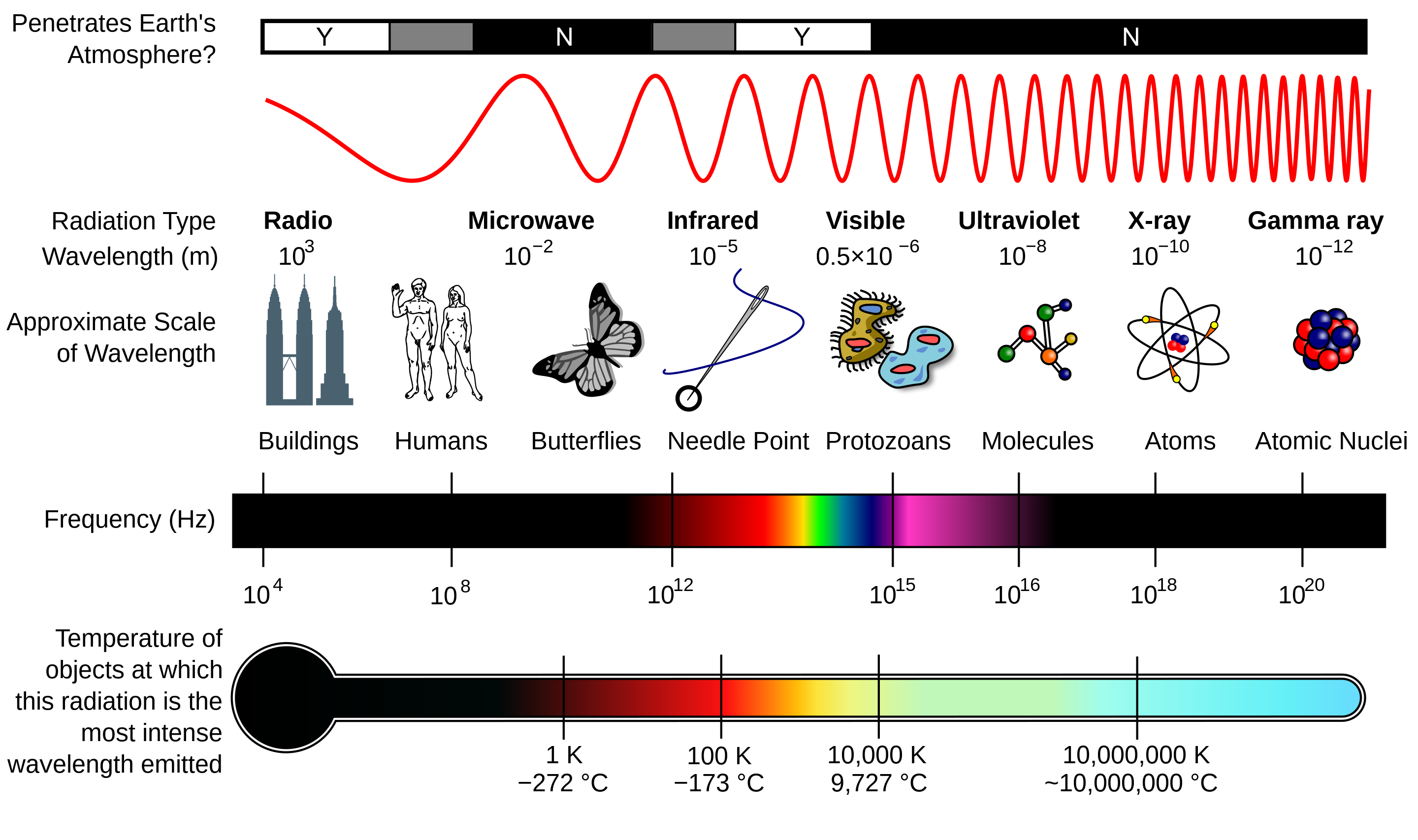

The electromagnetic spectrum represents the full range of electromagnetic radiation, spanning from the shortest, most energetic gamma rays to the longest, least energetic radio waves. While we’re most familiar with the narrow band of visible light, which ranges from 400 to 700 nanometers, this is only a tiny slice of the vast spectrum. The invisible radiation that surrounds us—infrared, ultraviolet, X-rays, and more—plays a crucial role in our understanding of the universe.

Electromagnetic Radiation

What makes the electromagnetic spectrum so fascinating is that all forms of electromagnetic radiation, no matter the wavelength or frequency, travel at the same speed: the speed of light (3 × 108 meters per second) in a vacuum. Yet, their vastly different wavelengths and frequencies allow them to interact with matter in diverse ways, revealing different aspects of the universe.Each type of radiation reveals something different about the universe. For example, X-rays help us see into the hearts of galaxies where black holes reside, while infrared radiation allows us to peer into cool dust clouds where stars are born. At either end of the spectrum are Gamma and Radio waves:

- Gamma rays are the shortest, most energetic waves, often produced by nuclear reactions and cosmic phenomena such as supernovae and black holes. These high-energy waves can penetrate through dense matter, providing insight into the most violent processes in the cosmos.

- Radio waves are at the opposite end of the spectrum, with the longest wavelengths. Despite their low energy, radio waves are invaluable in astronomy, penetrating dust clouds that block visible light and allowing astronomers to study the hidden cores of galaxies and nebulae.

To better understand the different types of electromagnetic radiation, the following table summarizes their wavelength ranges, the temperatures of objects that emit them, and their typical sources:

| Type of Radiation | Wavelength Range (nm) | Radiated by Objects at This Temperature | Typical Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gamma rays | Less than 0.01 | More than $10^8$ K | Produced in nuclear reactions; require very high-energy processes |

| X-rays | 0.01–20 | $10^6$–$10^8$ K | Gas in clusters of galaxies, supernova remnants, solar corona |

| Ultraviolet | 20–400 | $10^4$–$10^6$ K | Supernova remnants, very hot stars |

| Visible | 400–700 | $10^3$–$10^4$ K | Stars |

| Infrared | $10^3$–$10^6$ | 10–$10^3$ K | Cool clouds of dust and gas, planets, moons |

| Microwave | $10^6$–$10^9$ | Less than 10 K | Active galaxies, pulsars, cosmic background radiation |

| Radio | More than $10^9$ | Less than 10 K | Supernova remnants, pulsars, cold gas |

Applications in Astronomy

The electromagnetic spectrum is more than just a collection of different types of radiation—it’s a window into the universe. Each portion of the spectrum allows astronomers to observe different aspects of the cosmos, revealing phenomena that are invisible to the human eye. By harnessing the full range of electromagnetic waves, astronomers can study everything from the birth of stars to the behavior of black holes.

-

Radio Waves: With their long wavelengths, radio waves are capable of penetrating dense clouds of gas and dust that block visible light. This makes them invaluable for studying star-forming regions and the hidden cores of galaxies. Radio astronomy has led to groundbreaking discoveries, such as the cosmic microwave background radiation, the afterglow of the Big Bang. Radio telescopes like the Event Horizon Telescope have even achieved the remarkable feat of imaging the shadow of a black hole, a direct glimpse into one of the universe’s most enigmatic objects.

-

Infrared Radiation: Infrared light is emitted by cooler objects, such as brown dwarfs, planets, and clouds of gas and dust. This part of the spectrum is especially useful for observing regions of space that are obscured by dust in visible light, such as the nurseries where new stars are being born. Telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) are optimized for infrared observations and are expected to reveal previously hidden details of the early universe, as well as the atmospheres of exoplanets.

-

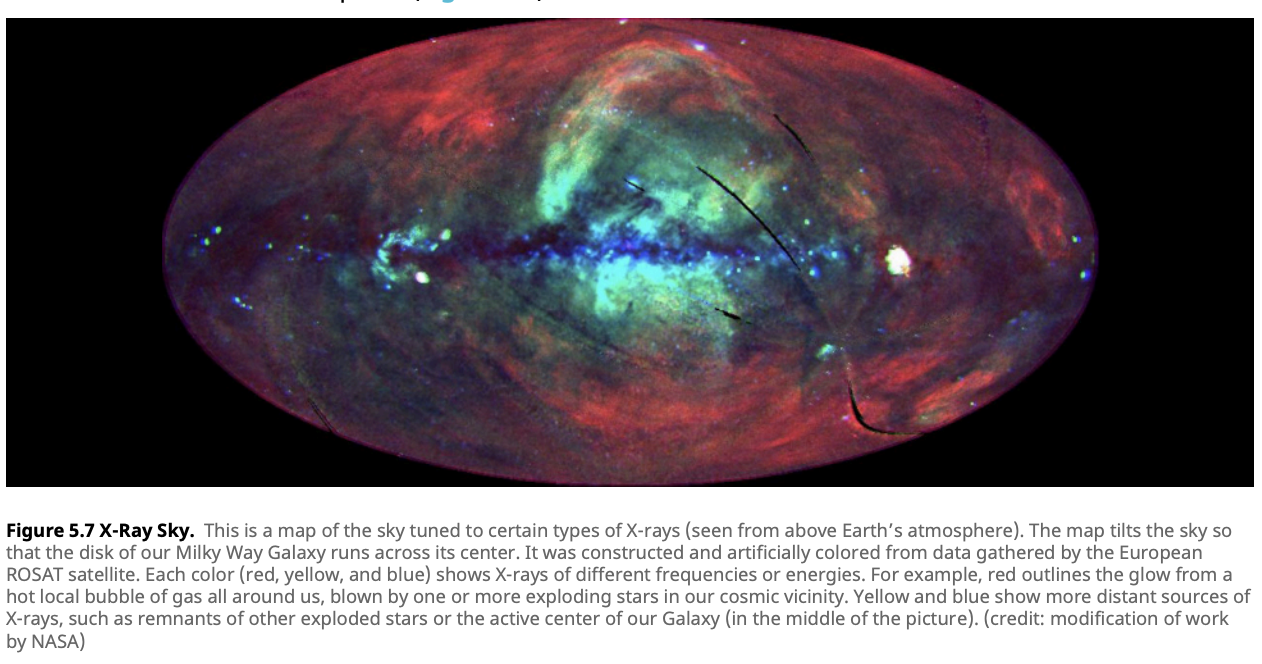

X-rays: X-rays are emitted by some of the most extreme phenomena in the universe, including supernovae, neutron stars, and black holes. These high-energy waves allow astronomers to observe the violent and energetic processes that are invisible in other wavelengths. NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, for instance, has captured images of supernova remnants, revealing shock waves and hot gas expanding into space. X-ray astronomy also plays a critical role in studying the environments around black holes, where matter is heated to millions of degrees before falling into the event horizon.

Photons and their Energy

Light is a fascinating phenomenon that exhibits both wave-like and particle-like properties, a duality that puzzled scientists for centuries. This concept, known as wave-particle duality, is central to our understanding of light and its behavior in the universe.

On the one hand, light behaves like a wave, capable of interference and diffraction. It travels through space in the form of electromagnetic waves, with properties such as wavelength and frequency. However, light also behaves like a particle, composed of discrete packets of energy called photons. Each photon carries a specific amount of energy, which is determined by the frequency of the light.

The relationship between the energy of a photon and its frequency is given by Planck’s equation:

\[E = hf\]

In this equation, $E$ represents the energy of the photon, $h$ is Planck’s constant ($6.626 \times 10^{-34}$ J·s), and $f$ is the frequency of the light. This equation reveals that higher-frequency light, such as ultraviolet or X-rays, has more energetic photons compared to lower-frequency light, such as infrared or radio waves.

Wave-particle duality plays a crucial role in many astronomical observations. For example, in the photoelectric effect, photons striking a material can release electrons from its surface. This effect, which supports the particle theory of light, is not only foundational in quantum physics but also has practical applications in technology, such as in solar cells that convert sunlight into electricity.

Example: Calculating the Energy of a Photon

Calculate the energy of a photon of ultraviolet light with a frequency of 7.5 × 1014 Hz.

- Identify the given values:

- Frequency, $f = 7.5 \times 10^{14}$ Hz

- Planck’s constant, $h = 6.626 \times 10^{-34}$ J·s

- Use Planck’s equation to calculate the energy of the photon: \(E = hf\) Substituting the given values: \(E = (6.626 \times 10^{-34} \, \text{J}\cdot\text{s}) \times (7.5 \times 10^{14} \, \text{Hz})\)

- Calculate the result: \(E = 4.97 \times 10^{-19} \, \text{J}\)

The energy of a photon of ultraviolet light with a frequency of $7.5 \times 10^{14}$ Hz is $4.97 \times 10^{-19}$ joules. This high-energy photon is capable of causing chemical reactions, such as those responsible for sunburn, and can be observed in astronomical phenomena such as the radiation from hot stars.

Interaction of Light with Matter

Light interacts with matter in several important ways, each of which plays a crucial role in both everyday life and astronomical observations. When light encounters a surface or passes through a material, it can be reflected, refracted, or absorbed, depending on the properties of the material and the angle of incidence.

-

Reflection: When light strikes a surface and bounces back, we call this reflection. A familiar example is light reflecting off a mirror, allowing us to see ourselves. Reflection also occurs in astronomical instruments, such as reflecting telescopes, which use mirrors to collect and focus light from distant stars and galaxies.

-

Refraction: Refraction occurs when light passes from one medium into another, bending in the process. This bending happens because light changes speed as it moves from one material to another. A common example is the way a straw appears bent when partially submerged in water. Refraction is a fundamental principle in refracting telescopes, which use lenses to bend and focus light.

-

Absorption: In absorption, light is taken in by matter and converted into other forms of energy, such as heat. This process is why dark surfaces, like asphalt, feel hot after being exposed to sunlight. In astronomy, the absorption of light by dust and gas in space can obscure celestial objects, requiring astronomers to use different wavelengths of light to see through these clouds.

Understanding these interactions is essential for designing telescopes and other astronomical instruments. Reflecting telescopes, for example, use large mirrors to collect faint light from distant objects, while refracting telescopes rely on lenses to bend light and focus it onto a detector. These principles allow astronomers to gather and analyze light from across the universe, providing insights into the nature of stars, galaxies, and other celestial phenomena.

Wavelength Absorption

Remember, different materials absorb different wavelengths of light. This is why some telescopes are specifically designed to observe certain types of radiation, like X-rays or infrared light. Since Earth's atmosphere absorbs much of this radiation, space-based observatories are required to capture these wavelengths and reveal what lies beyond the visible spectrum.Check Your Understanding

- Electromagnetic Spectrum: What distinguishes one type of electromagnetic radiation from another? Describe the main categories (or bands) of the electromagnetic spectrum and provide an example of an astronomical object or phenomenon observed in each band.

- Light Interaction with Matter: Explain why a glass prism disperses light into a spectrum of colors. How is this principle used in astronomical spectrometers to analyze the light from stars and galaxies?

- Observing in Different Wavelengths: With what type of electromagnetic radiation would you observe:

- A. A star with a temperature of 5800 K (like our Sun)?

- B. A gas heated to a temperature of one million K, such as in the solar corona?

- C. A cool planet or moon that radiates in the infrared?

- Radiation and Health: Why is it dangerous to be exposed to X-rays but not (or at least much less) dangerous to be exposed to radio waves? How do astronomers safely observe X-rays from distant cosmic sources?

- Atmospheric Transparency: Astronomers want to make maps of the sky showing sources of X-rays or gamma rays. Explain why these observations must be made from above Earth’s atmosphere. What type of telescopes are used for this purpose?

- A radio telescope is tuned to observe a distant galaxy emitting radio waves at a frequency of 1420 MHz (this is the frequency of neutral hydrogen, a key tracer of galactic structure). What is the wavelength of this radiation?

- You observe a star emitting red light with a wavelength of 656 nm (the H-alpha line, common in many stars). What is the frequency of this light?

- A gamma-ray burst is detected with a photon frequency of $2.4 \times 10^{21}$ Hz. What is the energy of one photon from this gamma-ray burst?

- A space telescope is observing an exoplanet in infrared light with a wavelength of 10 micrometers. What is the frequency of this radiation? How does this help astronomers study the temperature and composition of the exoplanet?

- The Hubble Space Telescope captures an image of a supernova in ultraviolet light with a wavelength of 250 nm. Calculate the energy of a photon at this wavelength. Why is ultraviolet light particularly useful for studying hot, young stars?

Resources

- Astronomy (2016). Andrew Fraknoi, David Morrison, and Sidney C. Wolff.