Stars are the building blocks of galaxies, and understanding their life cycle provides crucial insights into the workings of the universe. From the brilliant birth of a star to its final breath as a stellar remnant, the evolution of stars is a complex and fascinating journey governed primarily by one key factor: mass. In this lesson, we will explore how the initial mass of a star dictates its life path, the stages stars go through, and the remnants they leave behind.

Video

Watch this video for an introduction to stellar evolution and the Hertzsprung-Russell (H-R) Diagram. It provides visual aids and explanations that will help you understand the key concepts covered in this lesson. I recommend watching it at x1.5 speed!

Initial Mass and Its Impact on Stellar Evolution

The most important factor in determining a star’s evolution is its initial mass. The initial mass determines not only how long the star will live but also the different stages it will go through and its final fate. Stars are classified into three main categories based on their mass:

- Low-mass stars (up to 0.5 solar masses): These stars have long lifespans, typically tens of billions of years.

- Intermediate-mass stars (between 0.5 and 8 solar masses): These stars have moderate lifespans, ranging from hundreds of millions to a few billion years.

- High-mass stars (greater than 8 solar masses): These stars have short but dramatic lifespans, often only a few million years.

Why Does Mass Matter?

The greater the mass of a star, the higher the core temperature and pressure. This means that high-mass stars can sustain more vigorous nuclear fusion, leading to shorter lifespans but more spectacular end-of-life events, such as supernovae. In contrast, low-mass stars burn their fuel more slowly, leading to longer lifespans and more peaceful ends as white dwarfs.

Stellar Lifetimes

A low-mass star like our Sun will live for approximately 10 billion years, slowly fusing hydrogen into helium. In contrast, a massive star 20 times the mass of the Sun might live for only 10 million years before exploding as a supernova.The Hertzsprung-Russell (H-R) Diagram as a Tool for Understanding Stellar Evolution

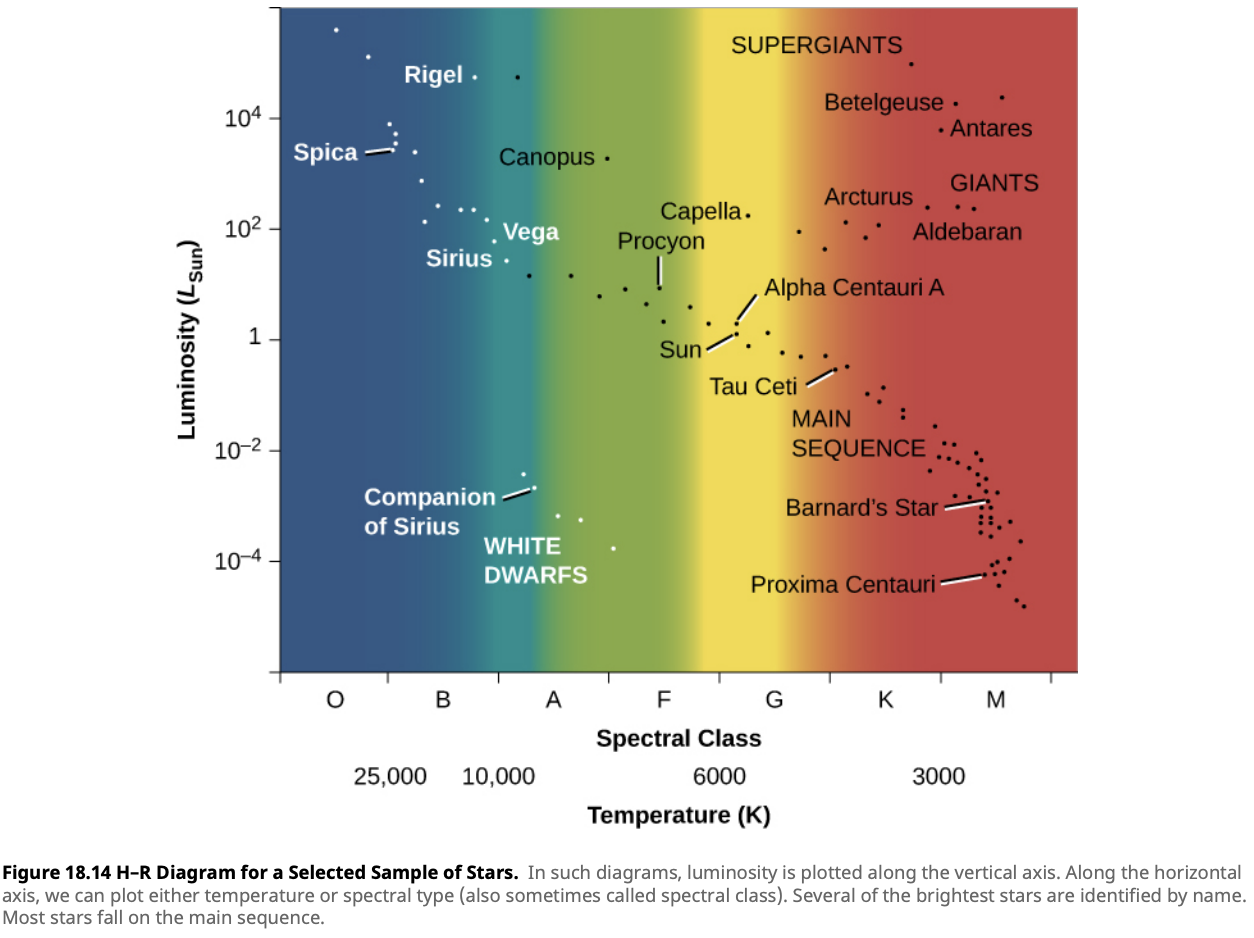

The Hertzsprung-Russell (H-R) Diagram is one of the most important tools in astronomy for understanding stellar evolution. The diagram plots stars according to their luminosity and surface temperature, revealing distinct patterns that correspond to different stages of stellar life.

Key Regions of the H-R Diagram:

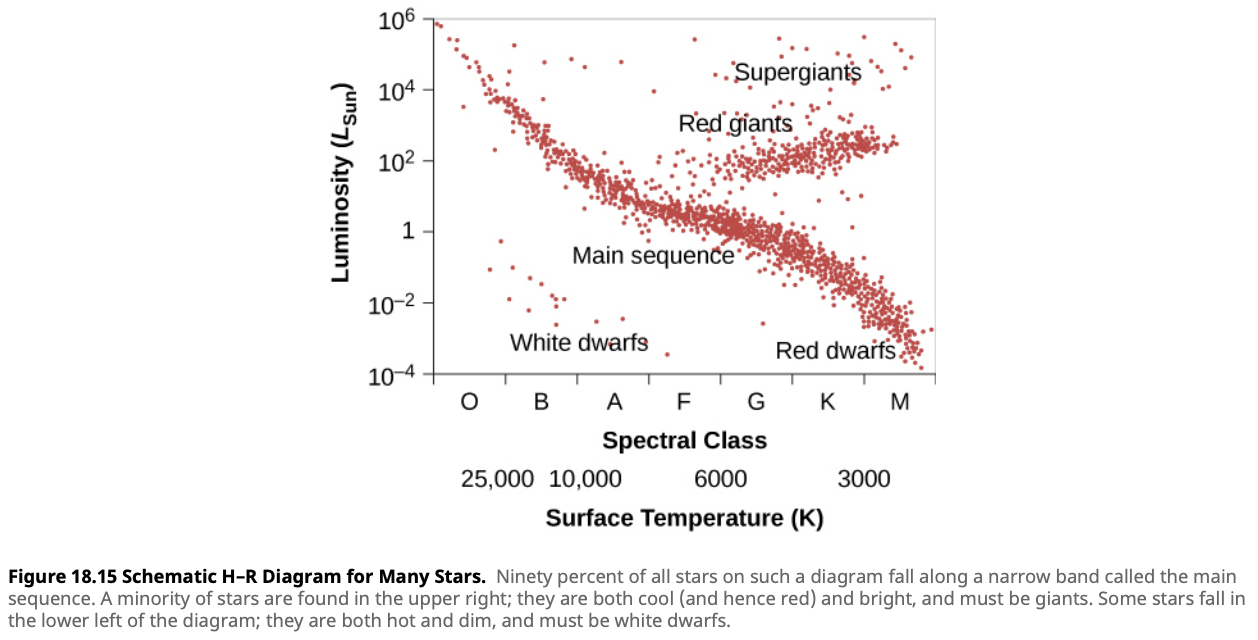

- Main Sequence: Where stars spend most of their lives, fusing hydrogen into helium. About 90% of stars fall on the main sequence, with their position determined by mass—more massive stars are hotter and more luminous, while low-mass stars are cooler and dimmer.

- Red Giants and Supergiants: Large, cool stars that have exhausted their hydrogen and moved on to fuse heavier elements. These stars occupy the upper-right region of the diagram, indicating high luminosity despite their relatively cool surface temperatures.

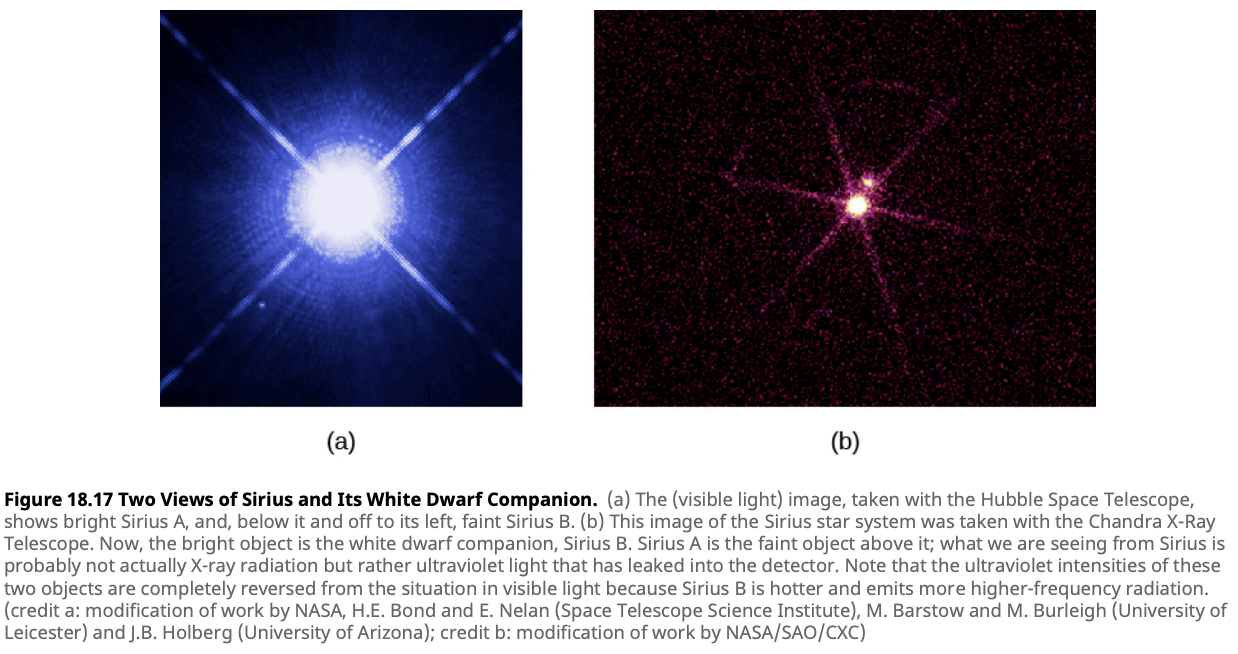

- White Dwarfs: Hot but dim remnants of low- and intermediate-mass stars, found in the lower-left region of the diagram. These stars are small but have very high surface temperatures.

Stellar Radii and the H-R Diagram:

The H-R Diagram also allows astronomers to infer stellar radii. If two stars have the same surface temperature but one is more luminous, the more luminous star must have a larger radius. This explains why supergiants can be cool but extremely luminous—they have enormous surface areas. Conversely, white dwarfs are hot but dim because of their small size.

Distribution of Stars:

It’s important to recognize that the distribution of stars on the H-R Diagram does not fully represent the true population of stars in the universe. While many stars we observe are on the main sequence, faint stars like red dwarfs are underrepresented due to their low brightness and distance from us. Understanding this helps astronomers make more accurate models of stellar populations.

The H-R Diagram

The H-R Diagram is often compared to the periodic table in chemistry—just as the periodic table organizes elements by their properties, the H-R Diagram organizes stars by their temperature and luminosity. It also helps astronomers estimate stellar radii and understand the diverse evolutionary paths of stars.

Main Sequence Evolution

Stars spend the majority of their lives on the main sequence, where they fuse hydrogen into helium in their cores. This is the most stable and longest phase of a star’s life. The position of a star on the main sequence depends on its mass: more massive stars are hotter and more luminous, placing them higher on the Hertzsprung-Russell (H-R) Diagram.

The main sequence phase ends when the star exhausts the hydrogen in its core. What happens next depends on the star’s mass.

Characteristics of Main-Sequence Stars

| Spectral Type | Mass (Sun = 1) | Luminosity (Sun = 1) | Temperature | Radius (Sun = 1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O5 | 40 | 7 × 105 | 40,000 K | 18 |

| B0 | 16 | 2.7 × 105 | 28,000 K | 7 |

| A0 | 3.3 | 55 | 10,000 K | 2.5 |

| F0 | 1.7 | 5 | 7500 K | 1.4 |

| G0 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 6000 K | 1.1 |

| K0 | 0.8 | 0.35 | 5000 K | 0.8 |

| M0 | 0.4 | 0.05 | 3500 K | 0.6 |

Tip:

On the H-R Diagram, stars on the main sequence form a diagonal line from the top left (hot, luminous stars) to the bottom right (cool, dim stars). Our Sun is a middle-aged main sequence star.Advanced Stages of Stellar Evolution

Once a star exhausts the hydrogen in its core, it enters the advanced stages of evolution. For low- and intermediate-mass stars, this means burning helium and possibly heavier elements, while high-mass stars go through a series of rapid fusion stages.

Helium and Heavier Element Fusion

- Helium Burning: After hydrogen is depleted, the core contracts and heats up, allowing helium to fuse into carbon and oxygen in a process called the triple-alpha process.

- Carbon, Oxygen, and Silicon Burning: In high-mass stars, the core continues to contract and heat up, enabling the fusion of heavier elements like carbon, oxygen, and silicon. These stages are much shorter and more energetic than hydrogen fusion.

Eventually, high-mass stars create iron in their cores, which cannot undergo fusion to release energy. This leads to a catastrophic core collapse, resulting in a supernova explosion.

High Mass Stars

A high-mass star may burn carbon in its core for only a few thousand years, while it spends millions of years fusing hydrogen on the main sequence.Post-Main Sequence Evolution

When a star exhausts the hydrogen in its core, it leaves the main sequence—the longest and most stable phase of its life. What happens next depends on the star’s mass, and the journey can take dramatically different paths. The post-main sequence evolution is where the true diversity of stellar life stories begins to unfold.

-

Low-Mass Stars: For a star like our Sun, after billions of years of stable hydrogen fusion, the core runs out of fuel, and the star can no longer hold itself together. The outer layers begin to expand and cool, turning the star into a red giant—an enormous, bloated version of its former self. During this phase, the star is shedding its outer layers in a stellar wind, leaving behind a hot, exposed core. Over time, the core cools and contracts, becoming a dense, Earth-sized object known as a white dwarf. The star’s brilliance fades, but it will continue to glow faintly for billions of years as it slowly radiates away its remaining heat.

-

Intermediate-Mass Stars: Stars with slightly more mass follow a similar path but with a bit more flair. These stars also become red giants, but as they expel their outer layers, they often create beautiful, glowing shells of gas known as planetary nebulae. These nebulae are lit up by the ultraviolet radiation from the hot core, creating some of the most stunning images in astronomy. Like their smaller cousins, these stars end up as white dwarfs, quietly cooling for the rest of eternity.

-

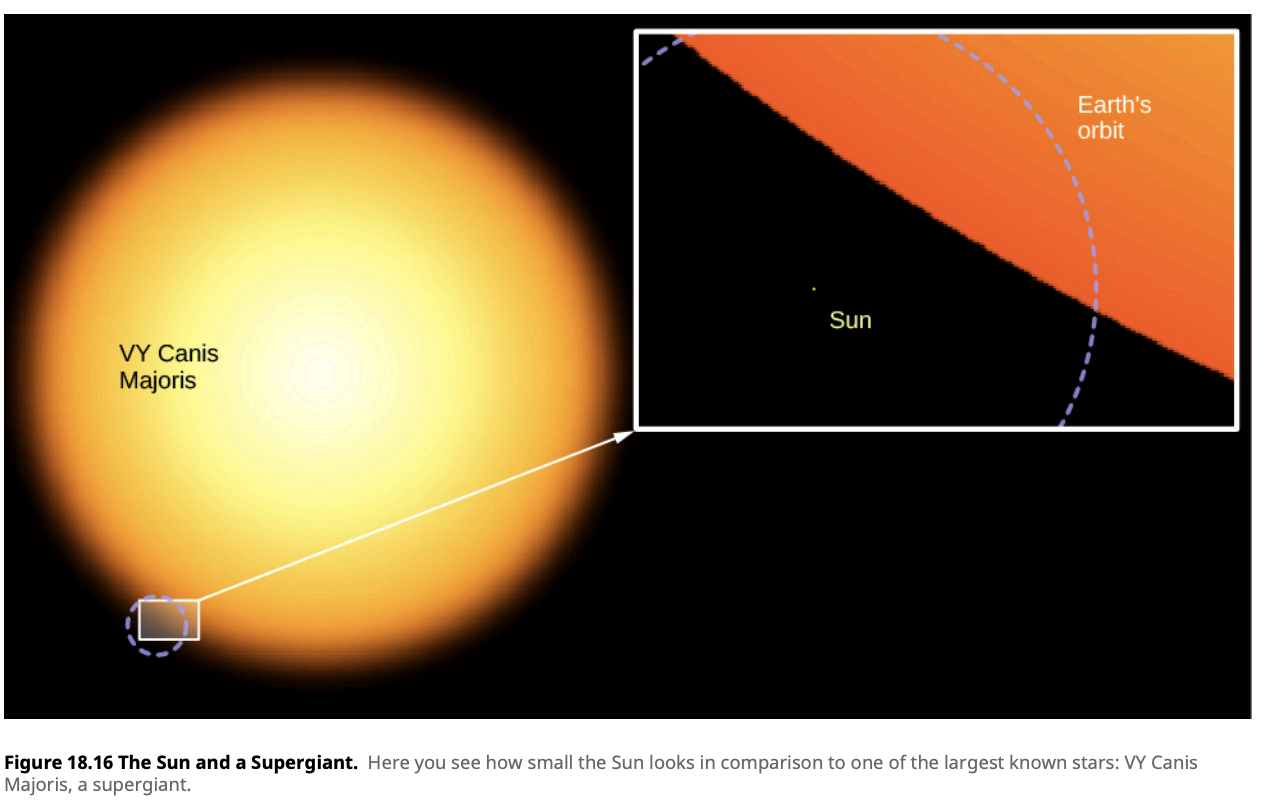

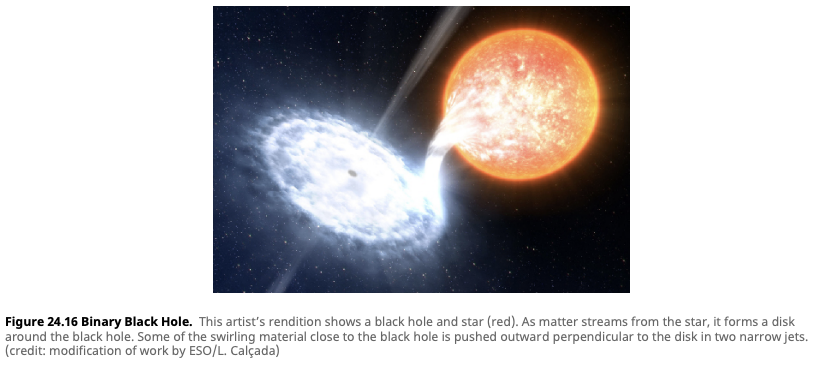

High-Mass Stars: The fate of high-mass stars, however, is far more dramatic. These stellar giants evolve into supergiants, with their cores burning through heavier and heavier elements—helium, carbon, oxygen, and so on—until they reach iron. Iron is a dead end for fusion, and without the energy from fusion to support it, the core collapses under its own gravity in a fraction of a second. This collapse triggers a supernova, one of the most powerful explosions in the universe. For a brief moment, the star shines brighter than an entire galaxy. What remains after this cosmic cataclysm is a dense core—either a neutron star or, if the star was massive enough, a black hole.

The Evolution of Stellar Remnants

The death of a star is not the end of its story. The remnants left behind after a star’s dramatic final act continue to exist, and each type of remnant tells a different tale of the star it once was.

- White Dwarfs: These remnants of low- and intermediate-mass stars are among the densest objects in the universe. Imagine compressing the mass of the Sun into a sphere the size of Earth—this is a white dwarf. The gravity at the surface of a white dwarf is so intense that a teaspoon of its material would weigh several tons on Earth. Though no longer capable of nuclear fusion, white dwarfs continue to glow faintly as they slowly cool over billions of years. Eventually, after a time far longer than the current age of the universe, they will cool to become cold, dark black dwarfs—essentially stellar embers that no longer emit light.

- Neutron Stars: When a high-mass star goes supernova, the core that remains can be crushed into an incredibly dense object called a neutron star. Imagine a star more massive than the Sun compressed into a sphere just 20 kilometers across. The densities involved are so extreme that a sugar-cube-sized amount of neutron star material would weigh as much as a mountain! Neutron stars also have some fascinating properties: many rotate extremely rapidly, and as they spin, they emit beams of radiation from their magnetic poles. When these beams sweep past Earth, we detect them as pulses of light, which is why these neutron stars are known as pulsars.

Did you know?

A neutron star has a density so extreme that a sugar-cube-sized amount of its material would weigh as much as a mountain.- Black Holes: For the most massive stars, even neutron stars are not dense enough to contain their cores after a supernova. The core collapses further, forming a black hole—a region of space where gravity is so strong that not even light can escape. These enigmatic objects warp space and time around them, and while we cannot see black holes directly, we can observe their effects on nearby matter. Gas and dust falling into a black hole are heated to extreme temperatures and emit X-rays, providing a glimpse of these mysterious cosmic objects. Black holes can continue to grow over time by swallowing up surrounding matter, merging with other black holes, or both, creating even more massive versions known as supermassive black holes found at the centers of galaxies.

Check Your Understanding

- Mass and Evolution: How does the initial mass of a star determine its life cycle and final fate?

- Fusion Processes: Why do more massive stars undergo faster fusion processes, leading to shorter lifespans?

- H-R Diagram: How can the Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram be used to track the life cycle of a star?

- Supernovae: What conditions lead to a supernova explosion, and what determines whether the remnant will be a neutron star or a black hole?

- Main Sequence Trends: Describe how the mass, luminosity, surface temperature, and radius of main-sequence stars change in value going from the “bottom” to the “top” of the main sequence.

-

Spectral Data Analysis: Review the spectral data for the five stars in the table below:

Star Spectrum 1 G, main sequence 2 K, giant 3 K, main sequence 4 O, main sequence 5 M, main sequence - Which is the hottest? Coolest? Most luminous? Least luminous? In each case, give your reasoning.

- Which is the hottest? Coolest? Most luminous? Least luminous? In each case, give your reasoning.

- Type-M Star: An astronomer discovers a type-M star with a large luminosity. How is this possible? What kind of star is it?

- Betelgeuse Density: Betelgeuse has a radius of 0.75 billion kilometers and a mass that is 15 times that of the Sun, how would its average density compare to that of the Sun? Use the definition of density, $ \text{density} = \frac{\text{mass}}{\text{volume}} $, where the volume is that of a sphere.

- Main Sequence Evolution: How do stars typically “move” through the main sequence band on an H–R diagram? Why?

Resources

- Astronomy (2016). Andrew Fraknoi, David Morrison, and Sidney C. Wolff.

- Foundations of Astrophysics (2010). Barbara Ryden, Bradley M. Peterson.