Elements are the fundamental building blocks of matter. Everything we see around us—from the air we breathe to the stars in the night sky—is made up of elements. But where do these elements come from? The answer lies within the stars.

In this lesson, we will explore how stars produce elements and how these elements evolve over time.

Video

Watch this video for an excellent introduction to the origin of elements.

Nucleosynthesis and the Origin of Elements

Nucleosynthesis is the process by which new atomic nuclei are created within stars. The story begins shortly after the Big Bang, approximately 13.7 billion years ago, when the universe was filled with hydrogen and a little bit of helium—the first two elements on the periodic table.

As the universe expanded, gravity caused hydrogen to clump together, forming the first stars. These stars, through nuclear fusion, began the process of creating new elements. The fusion processes that occur within stars are responsible for producing almost all the elements in the periodic table.

Hydrogen Burning and the Proton-Proton Chain

Note:

Remember that the term "burning" in astrophysics refers to nuclear fusion, not chemical combustion.We already learned about the simplest and most common fusion process in stars, which is hydrogen burning. This occurs through the proton-proton chain. This process dominates in stars like our Sun, where four hydrogen nuclei (protons) combine to form a single helium nucleus.

This chain reaction not only produces helium but also releases a significant amount of energy, which powers the star and balances the inward pull of gravity. This process can continue for billions of years, as in the case of our Sun, which is currently in the middle of its hydrogen-burning phase.

Helium Burning and the Triple-Alpha Process

As stars evolve and exhaust their hydrogen fuel, the core contracts and heats up, enabling the fusion of helium. This process is known as helium burning, and it occurs through the triple-alpha process.

The triple-alpha process can be described as follows:

- Formation of Beryllium-8:

- Two helium-4 nuclei (alpha particles) collide to form beryllium-8. The reaction can be represented as:

\[\text{He}^4 + \text{He}^4 \rightarrow \text{Be}^8\]

- Beryllium-8 ($\text{Be}^8$) is highly unstable and typically decays back into two helium nuclei within a fraction of a second. However, under the extreme conditions in the core of a star, if another helium-4 nucleus collides with the beryllium-8 before it decays, the next step occurs.

- Two helium-4 nuclei (alpha particles) collide to form beryllium-8. The reaction can be represented as:

- Formation of Carbon-12:

- The unstable beryllium-8 nucleus captures another helium-4 nucleus to form carbon-12. The reaction is:

\[\text{Be}^8 + \text{He}^4 \rightarrow \text{C}^{12} + \gamma\]

- This reaction releases a gamma-ray photon ($\gamma$), which carries away the excess energy from the fusion process.

- The unstable beryllium-8 nucleus captures another helium-4 nucleus to form carbon-12. The reaction is:

This sequence of reactions is the primary way that carbon, an essential element for life, is produced in stars. The creation of carbon and oxygen through the triple-alpha process marks a critical stage in the chemical evolution of the universe, as these elements are necessary for the formation of complex molecules and ultimately, life as we know it.

Advanced Nuclear Burning Stages

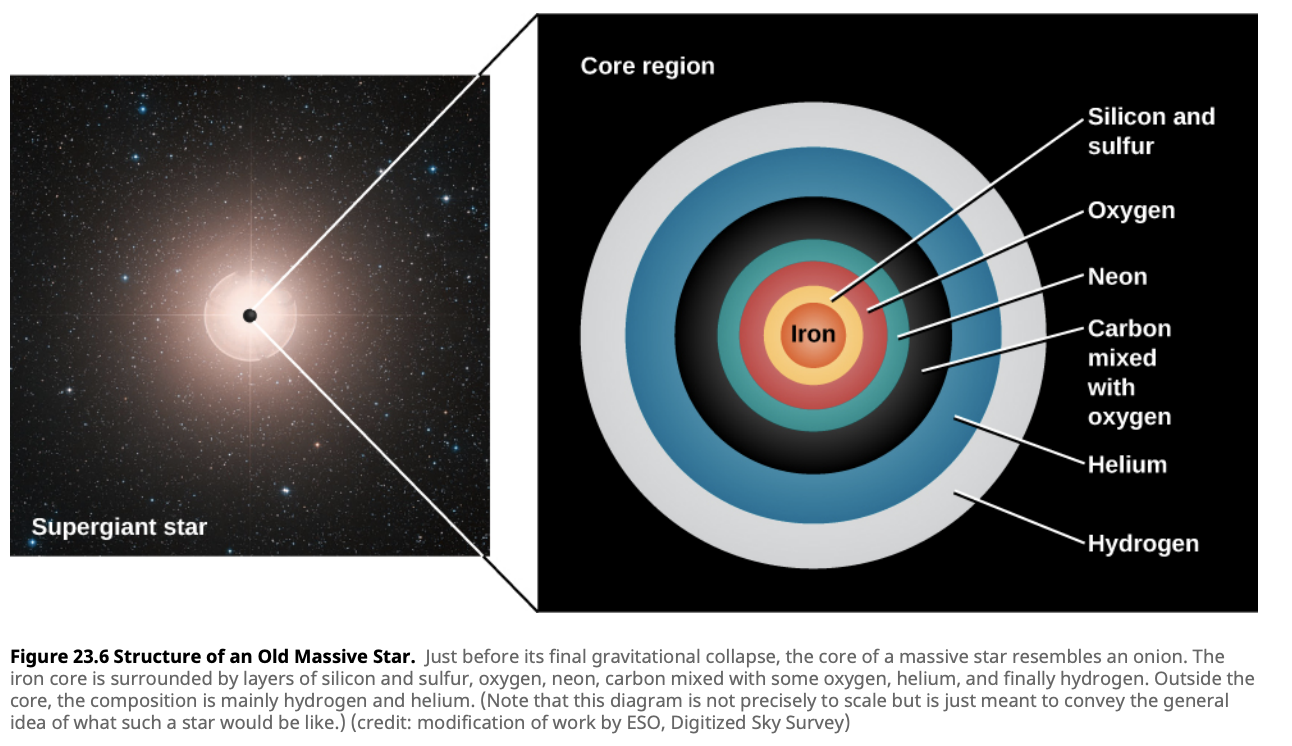

In more massive stars, after helium is exhausted, the core contracts further, and temperatures rise high enough to fuse heavier elements. These advanced nuclear burning stages include carbon burning, neon burning, oxygen burning, and silicon burning.

Each of these stages produces increasingly heavier elements, with silicon burning ultimately leading to the production of iron. Here’s a brief overview of these processes:

- Carbon Burning: Produces neon, sodium, and magnesium.

- Neon Burning: Produces oxygen and magnesium.

- Oxygen Burning: Produces silicon, sulfur, phosphorus, and magnesium.

- Silicon Burning: Produces elements up to iron.

Iron represents the end of the line for fusion in stars. Unlike lighter elements, fusing iron does not release energy; instead, it consumes energy. This is because iron has the most tightly bound nucleus, making further fusion energetically unfavorable. Once a star’s core is predominantly iron, it has reached a critical stage in its life cycle.

Given:

Mass of a Carbon-12 nucleus: $ m_{\text{C}} = 12.000 \, \text{u} $

Mass of a Magnesium-24 nucleus: $ m_{\text{Mg}} = 23.985 \, \text{u} $

Solution:

The fusion of two Carbon-12 nuclei forms one Magnesium-24 nucleus:

\[\text{C}^{12} + \text{C}^{12} \rightarrow \text{Mg}^{24}\]Calculate the mass difference between the initial and final nuclei:

\[\Delta m = (2 \times 12.000 \, \text{u}) - 23.985 \, \text{u}\] \[\Delta m = 24.000 \, \text{u} - 23.985 \, \text{u} = 0.015 \, \text{u}\]Convert this mass difference to kilograms using $1 \, \text{u} = 1.66054 \times 10^{-27} \, \text{kg}$:

\[\Delta m = 0.015 \, \text{u} \times 1.66054 \times 10^{-27} \, \text{kg/u}\] \[\Delta m \approx 2.49 \times 10^{-29} \, \text{kg}\]Now, apply Einstein’s mass-energy equivalence formula: $E = \Delta mc^2$

\[E = (2.49 \times 10^{-29} \, \text{kg}) \times (3 \times 10^8 \, \text{m/s})^2\] \[E \approx 2.24 \times 10^{-12} \, \text{J}\]Therefore, the energy released during the fusion of two Carbon-12 nuclei to form Magnesium-24 is approximately $2.24 \times 10^{-12}$ Joules.

Supernovae and the Creation of Heavy Elements

Imagine a colossal star, thousands of times more massive than our Sun, reaching the end of its life. After millions of years of burning through its nuclear fuel, the star’s core has fused lighter elements into progressively heavier ones, culminating in iron. At this point, the star faces a fundamental problem: iron is the dead end of nuclear fusion, which means the star can no longer generate the pressure needed to counteract the relentless pull of gravity.

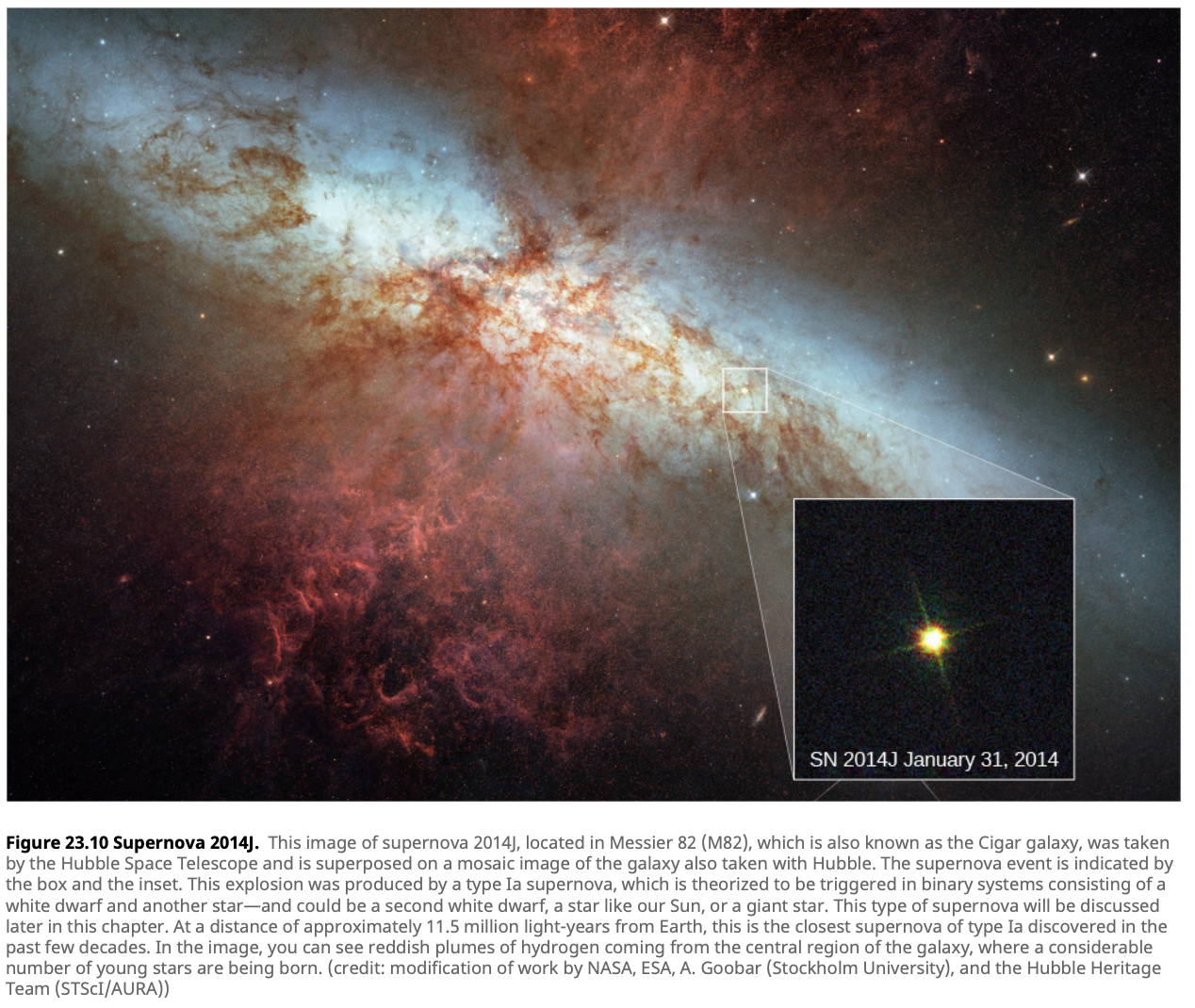

As gravity takes over, the core of the star collapses in a matter of seconds. This rapid implosion is so violent that it triggers a catastrophic explosion known as a supernova. In this single, fleeting moment, the star unleashes more energy than our Sun will produce over its entire 10-billion-year lifespan. The explosion is so bright that it can outshine entire galaxies and is visible across vast distances in the universe.

But a supernova is more than just a spectacular light show; it’s a cosmic forge, where the universe’s heaviest elements are born.

The r-Process: A Frenzy of Element Creation

During a supernova, the conditions become extraordinarily extreme—temperatures soar to billions of degrees, and the density of matter skyrockets. These conditions are perfect for a process known as rapid neutron capture, or the r-process. Here’s how it works:

As the star’s core collapses, an immense number of neutrons are suddenly available. In the blink of an eye, atomic nuclei start capturing these neutrons at a furious pace, much faster than they can decay. This rapid neutron bombardment leads to the formation of highly unstable, neutron-rich isotopes.

These isotopes are so unstable that they immediately undergo a series of beta decays, where neutrons convert into protons, transforming the element into a new, heavier one. This chain reaction continues, building up nuclei that are far heavier than iron—elements like gold, platinum, uranium, and thorium, which cannot be formed through fusion in any other stellar process.

Did You Know?

The gold in your jewelry and the uranium in nuclear reactors were formed in the violent explosion of a supernova billions of years ago!The Legacy of a Supernova: Seeding the Cosmos

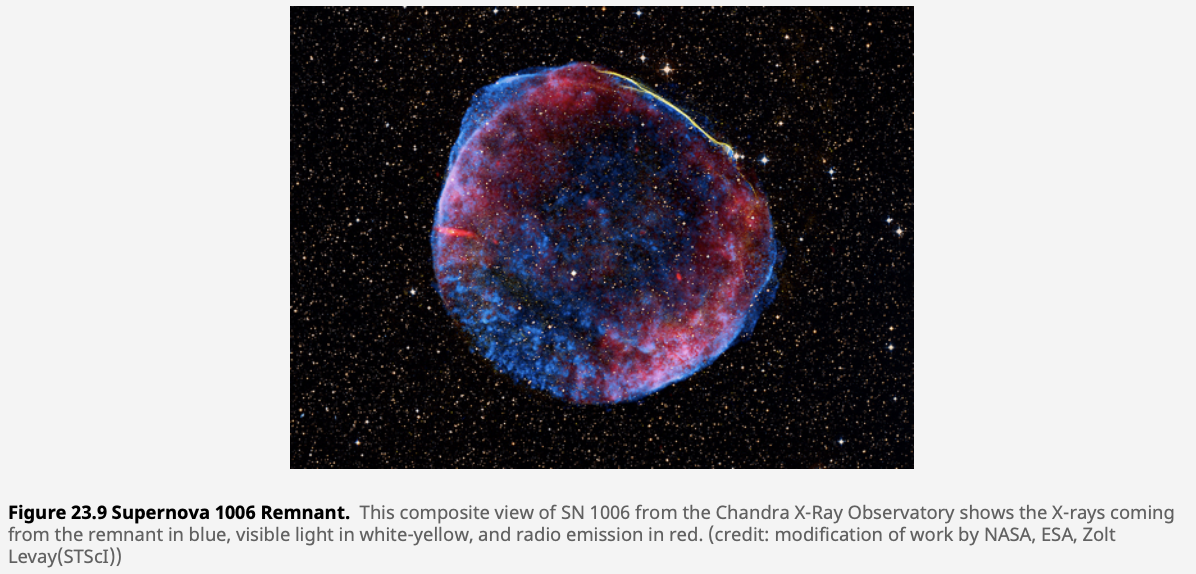

But the story doesn’t end with the creation of these heavy elements. The tremendous energy of the supernova not only creates these elements but also flings them out into space, scattering them across the galaxy. This interstellar debris, rich with newly minted heavy elements, mixes with the surrounding gas and dust, enriching the interstellar medium.

Over time, gravity will cause these enriched clouds of gas and dust to coalesce, eventually giving birth to new stars and planets. This means that the gold in your jewelry, the uranium in nuclear reactors, and the elements that make up the Earth and even your own body were all forged in the heart of a long-dead star, billions of years ago, and carried to our solar system by the remnants of a supernova.

Star Dust

You are quite literally made of star stuff! The carbon in your cells, the oxygen you breathe, and the iron in your blood were all created in stars billions of years ago. Every element heavier than hydrogen was born in the nuclear furnaces of stars or during the explosive deaths of massive stars. So, when you look up at the night sky, remember that the universe that created the stars also created you.Case Study: Supernova 1987A

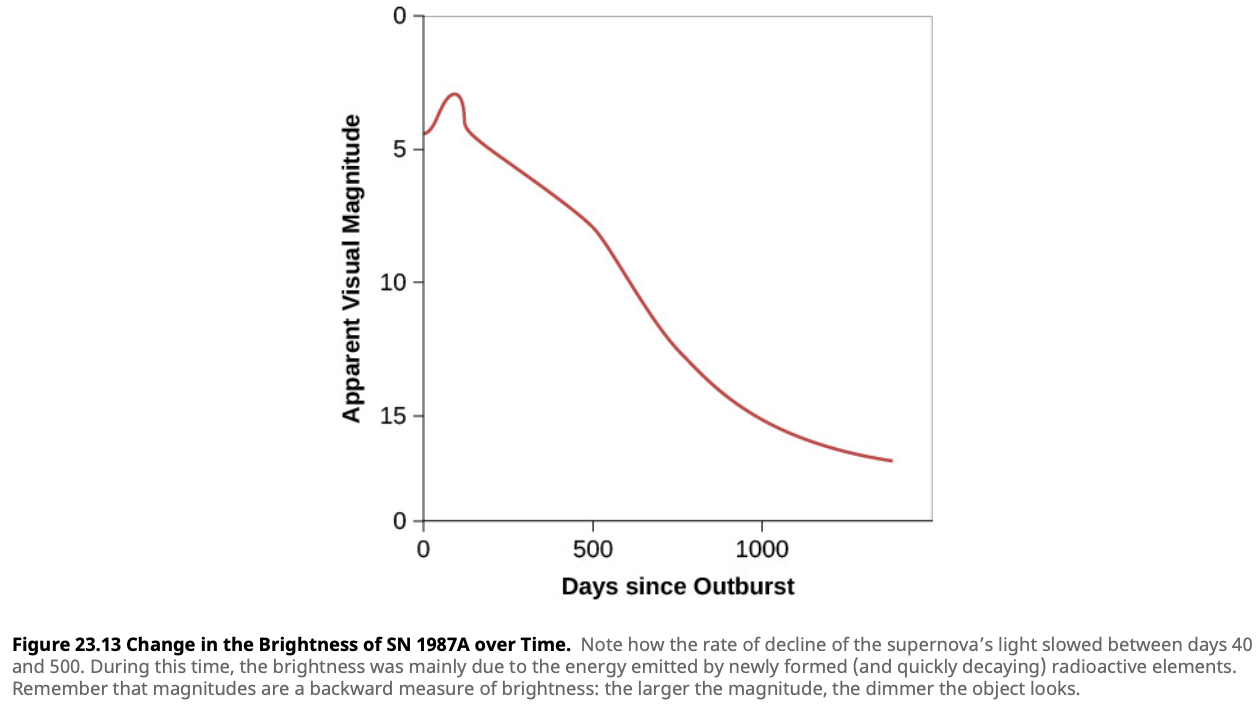

Supernova 1987A (SN 1987A) offers a rare look at the final stages of massive stars. Discovered on February 24, 1987, in the Large Magellanic Cloud, it was the closest supernova observed in nearly 400 years, just 160,000 light-years away. The progenitor star, Sanduleak -69° 202, was a blue supergiant about 20 times the mass of the Sun.

Stellar Evolution and the Supernova Event

Sanduleak -69° 202 lived most of its life fusing hydrogen into helium as a main-sequence star, with a luminosity 60,000 times that of the Sun. After exhausting its hydrogen, it expanded into a red supergiant and later reverted to a blue supergiant before collapsing in a type II supernova. The explosion was powerful enough to outshine its entire galaxy for weeks, ejecting the star’s outer layers and creating an expanding shell of gas and dust.

Observations and Legacy

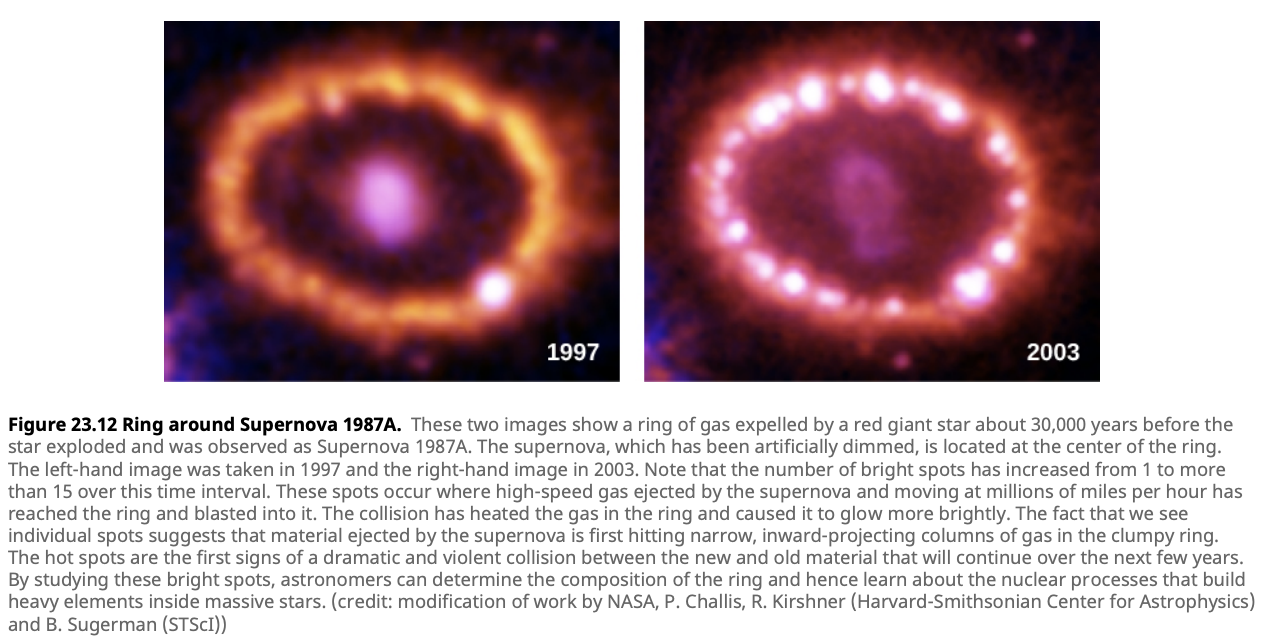

Post-explosion, the Hubble Space Telescope revealed a glowing ring of gas around SN 1987A, likely expelled during the star’s red supergiant phase. The collision of the supernova shockwave with this ring provided stunning visuals and valuable data. Additionally, the detection of neutrinos confirmed theoretical models of core-collapse supernovae, providing direct evidence of neutron star formation.

SN 1987A has greatly advanced our understanding of massive star life cycles, supernova mechanics, and nucleosynthesis—the formation of elements in stars. It remains a cornerstone in astrophysics, offering insights that continue to shape our knowledge of the cosmos.

Evolution of the Star That Exploded as SN 1987A

| Phase | Central Temperature (K) | Central Density (g/cm³) | Time Spent in This Phase |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen fusion | $40 \times 10^6$ | 5 | $8 \times 10^6$ years |

| Helium fusion | $190 \times 10^6$ | 970 | $10^6$ years |

| Carbon fusion | $870 \times 10^6$ | $170,000$ | 2000 years |

| Neon fusion | $1.6 \times 10^9$ | $3.0 \times 10^6$ | 6 months |

| Oxygen fusion | $2.0 \times 10^9$ | $5.6 \times 10^6$ | 1 year |

| Silicon fusion | $3.3 \times 10^9$ | $4.3 \times 10^7$ | Days |

| Core collapse | $200 \times 10^9$ | $2 \times 10^{14}$ | Tenths of a second |

Chemical Abundances in Stars

Evolution of Chemical Abundances and Star Populations

The chemical composition of stars has evolved significantly since the early universe, and this evolution is closely tied to the classification of stars into three distinct populations: Population I, II, and III stars. Each of these populations reflects a different stage in the history of the universe’s chemical enrichment.

Population III Stars: The First Generation

- Characteristics: Population III stars were the first stars to form in the universe, composed almost entirely of hydrogen and helium—the only elements produced during the Big Bang.

- Significance: These stars are believed to have been massive and short-lived, and while they have not been directly observed, their existence is inferred from theoretical models. Through their life cycles and eventual supernova explosions, Population III stars began the process of enriching the interstellar medium with heavier elements (metals).

- Legacy: The metals produced by Population III stars paved the way for the formation of subsequent generations of stars.

Population II Stars: The Metal-Poor Stars

- Characteristics: Formed from the material enriched by Population III stars, Population II stars contain small amounts of metals. These stars are typically found in the halo of our galaxy and in globular clusters, indicating their ancient origins.

- Significance: Population II stars represent an early stage of chemical enrichment, where the universe’s metallicity was still relatively low. Despite their low metal content, they played a crucial role in further enriching the interstellar medium.

Population I Stars: The Metal-Rich Stars

- Characteristics: Population I stars are the youngest and most metal-rich stars, including those found in the disk of our galaxy, such as our Sun. These stars formed from the heavily enriched material of previous generations of stars.

- Significance: The higher metallicity of Population I stars allows for the formation of more complex elements and compounds, contributing to the diversity of planetary systems and the potential for life.

The Evolution of Metallicity Over Time

As time progressed, each generation of stars contributed to the increasing metallicity of the universe. Population III stars initiated the enrichment process, Population II stars continued it, and Population I stars now represent the most chemically evolved stars. This gradual increase in metal content has led to more complex chemical compositions in later star-forming regions, influencing everything from star formation processes to the potential for life in the universe.

Understanding the differences between these star populations not only helps astronomers trace the history of chemical enrichment in the universe but also provides insights into the conditions under which different generations of stars and planetary systems have formed.

Check Your Understanding

-

Describe the significance of the triple-alpha process in the context of cosmic evolution. Why is this process crucial for the existence of life?

-

Differentiate between Population I, II, and III stars in terms of their metallicity and significance in the history of the universe.

-

Calculate the energy released when four protons (hydrogen nuclei) fuse to form a helium-4 nucleus in the proton-proton chain. The mass of a proton is $1.00728 \, \text{u}$, and the mass of a helium-4 nucleus is $4.00260 \, \text{u}$. Use $1 \, \text{u} = 1.66054 \times 10^{-27} \, \text{kg}$ and $c = 3 \times 10^8 \, \text{m/s}$.

-

Consider a massive star at the end of its life cycle, primarily composed of iron in its core. Discuss what will happen to this star and why iron represents the end of fusion processes in stars.

- Arrange the following stars in order of their evolution:

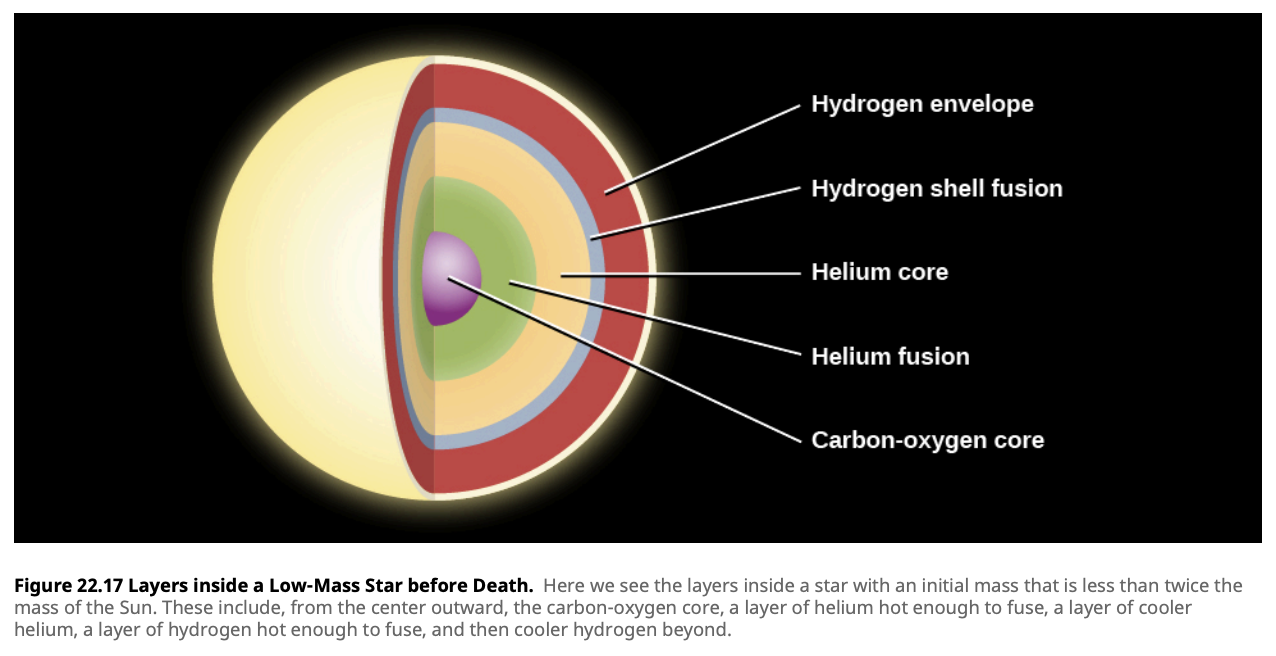

- A. A star with no nuclear reactions going on in the core, which is made primarily of carbon and oxygen.

- B. A star of uniform composition from center to surface; it contains hydrogen but has no nuclear reactions going on in the core.

- C. A star that is fusing hydrogen to form helium in its core.

- D. A star that is fusing helium to carbon in the core and hydrogen to helium in a shell around the core.

- E. A star that has no nuclear reactions going on in the core but is fusing hydrogen to form helium in a shell around the core.

-

Using the triple-alpha process, calculate the energy released when three helium-4 nuclei fuse to form one carbon-12 nucleus. The mass of a helium-4 nucleus is $4.00260 \, \text{u}$, and the mass of a carbon-12 nucleus is $12.000 \, \text{u}$.

-

The ring around SN 1987A (Figure 23.12) initially became illuminated when energetic photons from the supernova interacted with the material in the ring. The radius of the ring is approximately 0.75 light-year from the supernova location. How long after the supernova did the ring become illuminated?

-

A supernova can eject material at a velocity of 10,000 km/s. How long would it take a supernova remnant to expand to a radius of 1 AU? How long would it take to expand to a radius of 1 light-year? Assume that the expansion velocity remains constant and use the relationship: expansion time = distance / expansion velocity.

- A supernova remnant was observed in 2007 to be expanding at a velocity of 14,000 km/s and had a radius of 6.5 light-years. Assuming a constant expansion velocity, in what year did this supernova occur?

Resources

- Astronomy (2016). Andrew Fraknoi, David Morrison, and Sidney C. Wolff.

- Foundations of Astrophysics (2010). Barbara Ryden and Bradley M. Peterson.