Molecular clouds are vast, dark expanses of space, filled with cold, dense clouds of gas and dust. These molecular clouds serve as nurseries for star formation. Over millions of years, these clouds will collapse under their own gravity, eventually igniting nuclear fusion and giving birth to new stars. The story of star formation is a tale of transformation, from the silent, shadowy depths of a molecular cloud to the blazing brilliance of a newborn star.

Video

Watch this video for a detailed description of the star formation process.

The Birthplace of Stars: Molecular Clouds

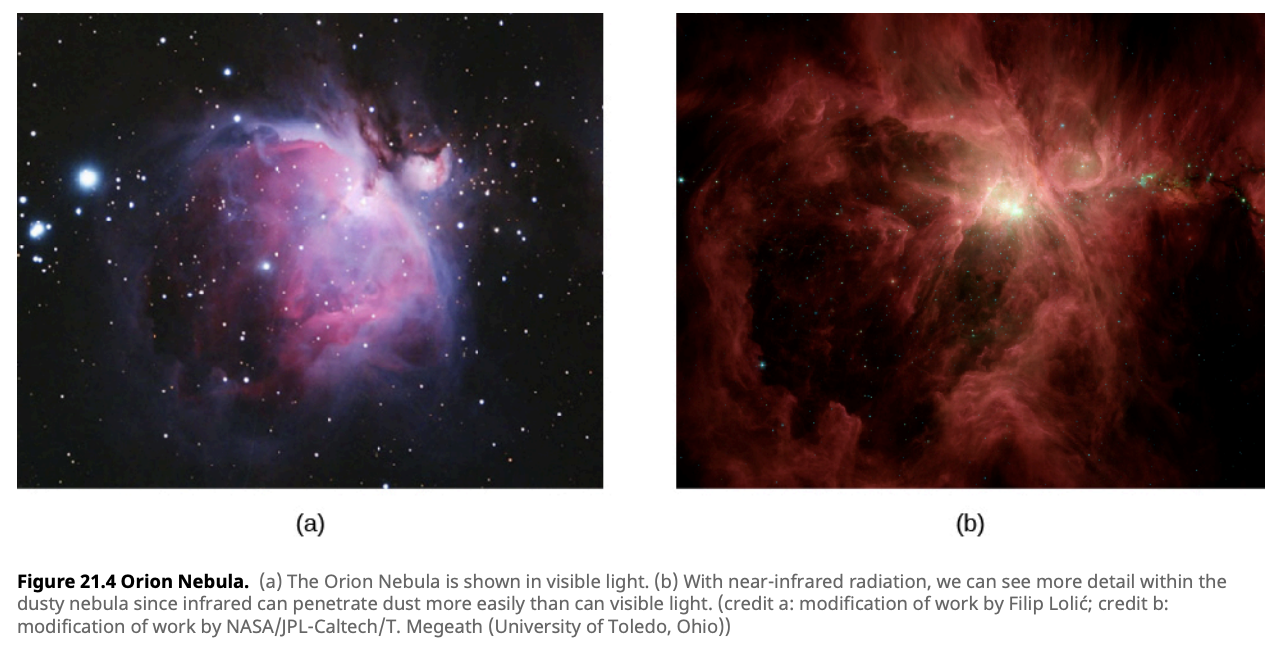

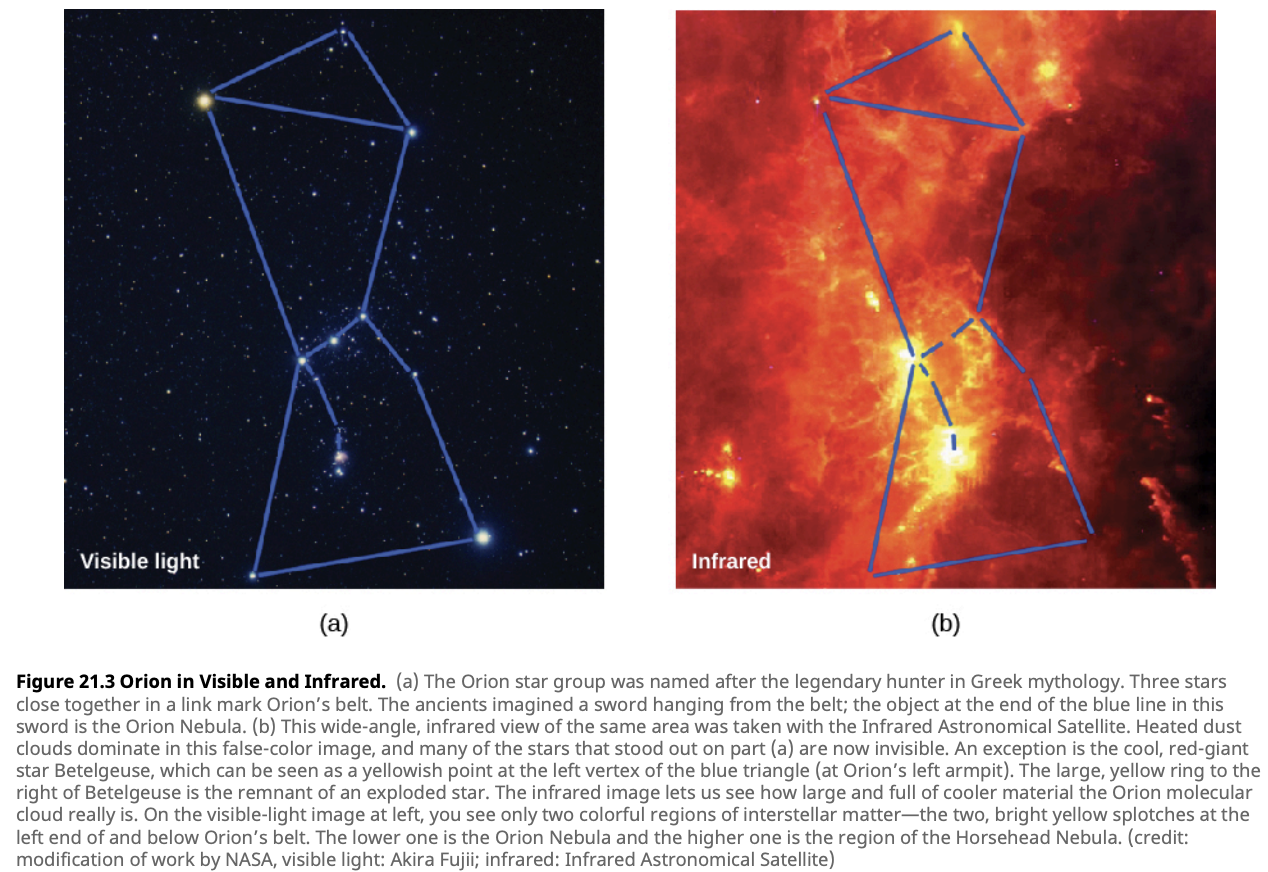

The Orion Nebula is a glowing cloud visible even to the naked eye. This stellar nursery, like many others, is a molecular cloud—a region teeming with the raw materials for star formation. These clouds, composed mainly of molecular hydrogen, are frigid, with temperatures barely above absolute zero, and dense, harboring the seeds of countless future stars.

Deep within these clouds, the force of gravity begins to pull the gas and dust inward. This inward pull creates regions of higher density, known as clumps. These clumps are the starting point of a star’s life.

Did You Know? The Orion Nebula, visible to the naked eye, is one of the most famous star-forming regions and serves as an excellent example of a molecular cloud.

Characteristics of Molecular Clouds:

- Temperature: 10-20 K, colder than any place on Earth.

- Composition: Mostly hydrogen, with helium and trace elements.

- Density: High compared to the surrounding space, a fertile ground for star birth.

Examples of Molecular Clouds:

- Orion Nebula: A well-known star-forming region.

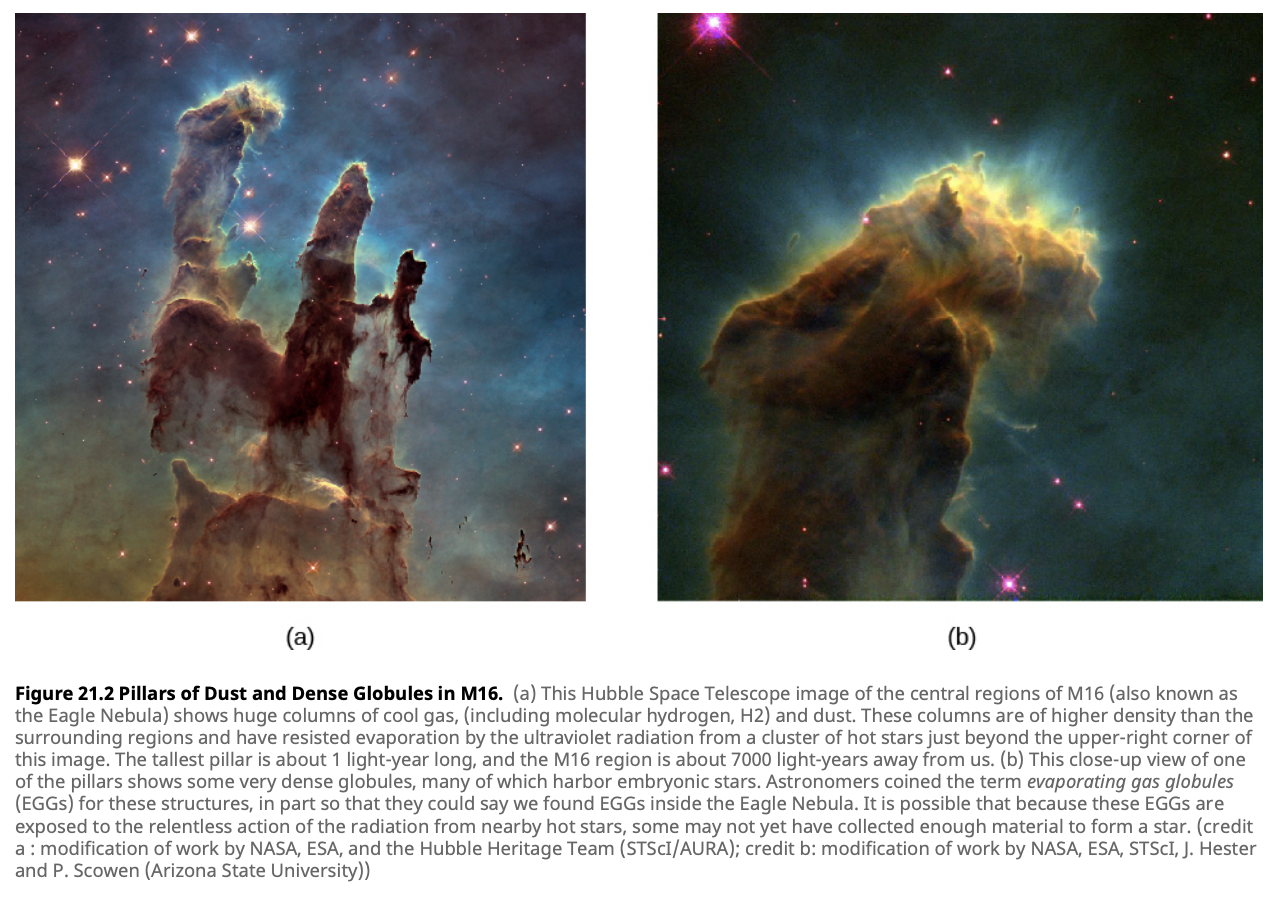

- Eagle Nebula: Famous for the “Pillars of Creation,” towering columns of gas sculpted by intense radiation from young, hot stars.

Stages of Star Formation

The birth of a star is a cosmic tale of transformation, where the interplay of gravity, pressure, and temperature orchestrates a stunning sequence of events. Let’s delve into the fascinating stages that lead from a cold molecular cloud to a radiant main sequence star.

1. Gravitational Collapse: In the vast expanses of space, molecular clouds, teeming with gas and dust, float in silence. This peace can be shattered by a powerful event, such as a supernova explosion, sending shockwaves through the cloud. These shockwaves compress regions within the cloud, causing them to begin to collapse under their own gravity. This marks the first step in the birth of a star.

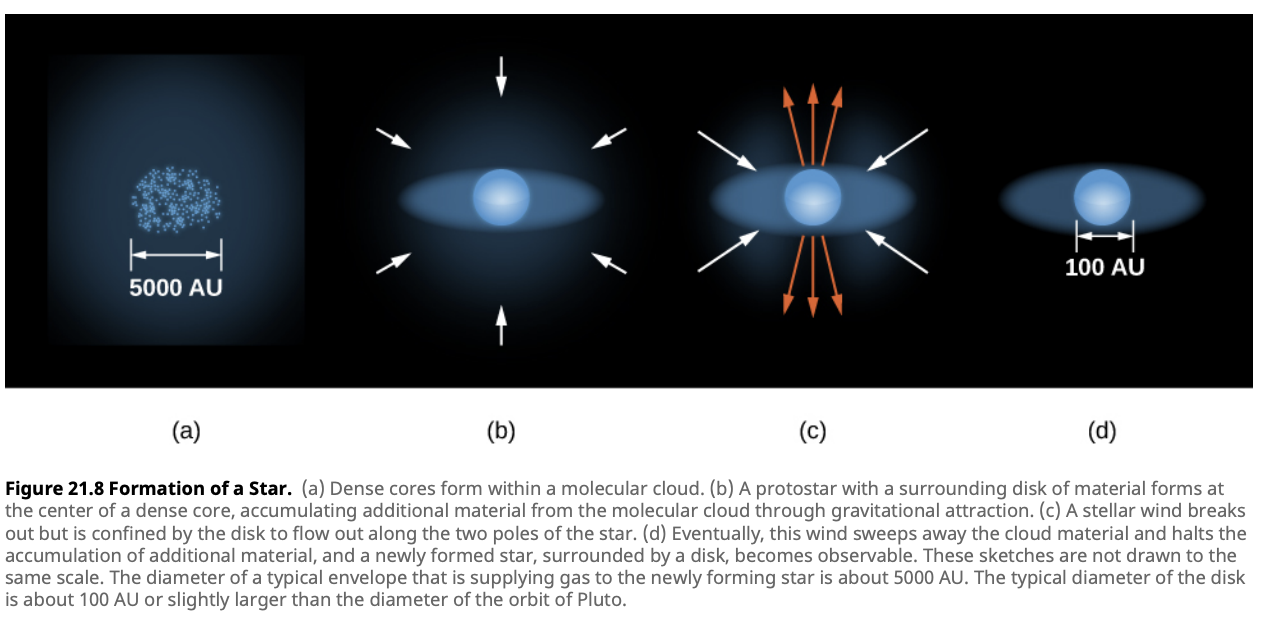

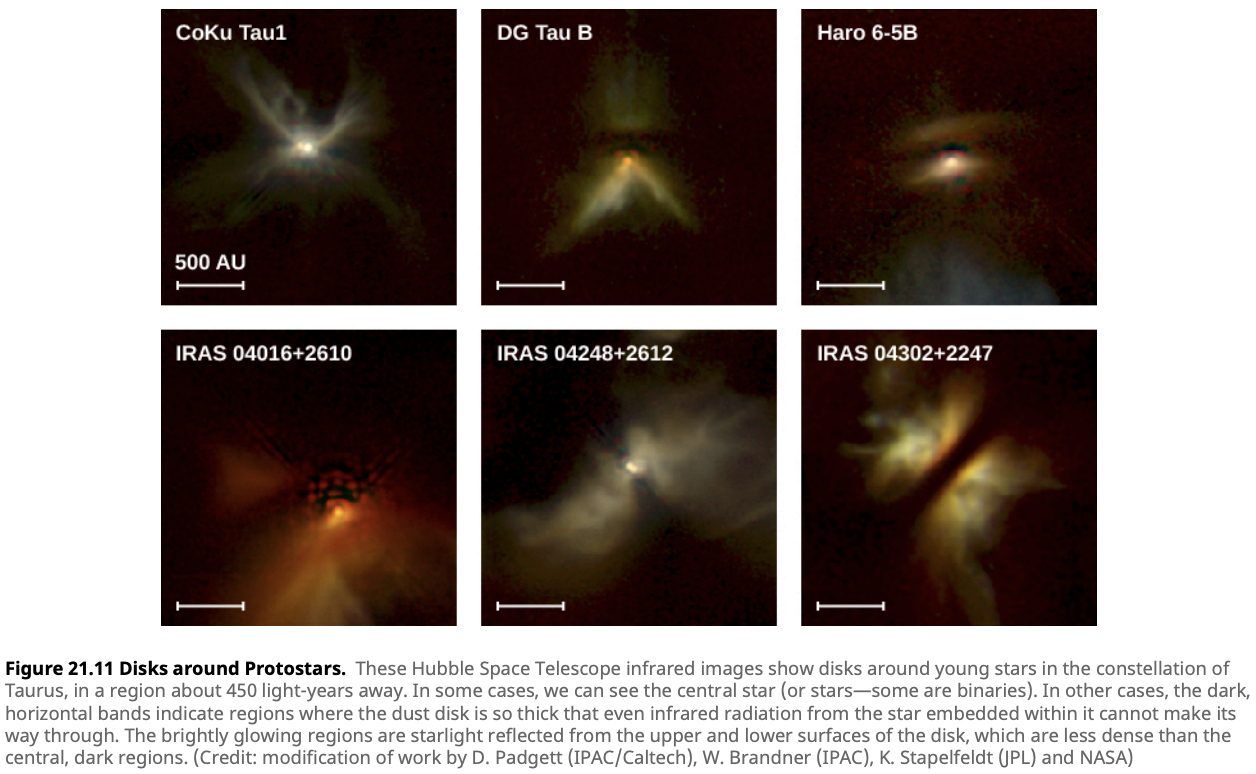

2. Accretion Disk and Protostar Formation: As the cloud collapses, it fragments into dense clumps. The core of each clump continues to contract, spinning faster due to the conservation of angular momentum—similar to a figure skater pulling in their arms to spin faster. This rapid rotation prevents material from falling directly onto the core, instead forming a rotating disk around it. At the center of this disk, a hot, dense region forms: the protostar.

3. Stellar Wind and Angular Momentum Transfer: The young star generates a stellar wind—a stream of charged particles that escapes along the magnetic field lines. This wind carries away excess angular momentum, allowing the star to continue accreting material from the disk without spinning too rapidly. The wind escapes most effectively along the poles, creating striking bipolar outflows that can be observed as jets of high-speed gas.

4. Planet Formation within the Disk: Within the disk, dust grains begin to stick together, forming planetesimals—small, solid objects. These planetesimals collide and merge, gradually building up into planets. Meanwhile, the remaining gas and dust are gradually blown away by the stellar wind, clearing the surroundings and leaving a nascent planetary system orbiting the young star.

The Role of Angular Momentum

Angular momentum is a measure of the amount of rotation an object has, considering its mass, shape, and speed. It’s crucial for understanding the behavior of rotating systems, from spinning tops to orbiting planets.

Think of a figure skater performing a spin. When the skater pulls their arms close to their body, they spin faster. This happens because angular momentum is conserved. For the skater, pulling in their arms reduces their moment of inertia, which a measure of how spread out their mass is relative to the axis of rotation. To keep the angular momentum constant, their rotation speed increases.

Similarly, as the cloud of gas and dust contracts, it spins faster due to the conservation of angular momentum.

Angular Momentum Formula: \(L = I \cdot \omega\) where $L$ is angular momentum

$I$ is the moment of inertia

and $\omega$ is the angular velocity (how fast the object is spinning, measured in radians per second).

Understanding Moment of Inertia

The moment of inertia ($I$) is a measure of an object’s resistance to changes in its rotation and it depends on both the mass of the object and how that mass is distributed relative to the axis of rotation. For example, it’s easier to spin a figure skater with their arms close to their body than when their arms are extended. This is because pulling the arms in reduces the moment of inertia, allowing for faster rotation.

- High Moment of Inertia: Objects with mass distributed far from the axis of rotation, which makes it harder to spin.

- Low Moment of Inertia: Objects with mass concentrated close to the axis of rotation, which makes it easier to spin.

Common Moment of Inertia Formulas:

- Solid Sphere: $I = \frac{2}{5} m r^2$

- Thin Disk: $I = \frac{1}{2} m r^2$

- Thin Rod (rotating about its end): $I = \frac{1}{3} m L^2$

- Thin Rod (rotating about its center): $I = \frac{1}{12} m L^2$

Conservation of Angular Momentum

The conservation of angular momentum is a fundamental principle in physics. It states that if no external torque (twisting force) acts on a system, the total angular momentum of that system remains constant. This principle plays a crucial role in the formation of stars.

As a molecular cloud collapses, it starts to spin faster, much like our figure skater. This increase in rotation speed is due to the conservation of angular momentum.

Given:

Mass of the accretion disk, $ m = 2 \times 10^{30} \, \text{kg} $ (approximately the mass of the Sun)

Initial radius of the disk, $ r_1 = 1000 \, \text{AU} $ (1 AU = $1.496 \times 10^{11} \, \text{m}$)

Final radius of the disk, $ r_2 = 100 \, \text{AU} $

Initial rotation speed, $ \omega_1 = 1 \times 10^{-3} \, \text{rad/s} $

Solution:

First, convert the radii to meters:

\[r_1 = 1000 \, \text{AU} = 1000 \times 1.496 \times 10^{11} \, \text{m} = 1.496 \times 10^{14} \, \text{m}\] \[r_2 = 100 \, \text{AU} = 100 \times 1.496 \times 10^{11} \, \text{m} = 1.496 \times 10^{13} \, \text{m}\]Use the conservation of angular momentum:

\[L_1 = L_2\] \[I_1 \cdot \omega_1 = I_2 \cdot \omega_2\]The moment of inertia for a thin disk is given by:

\[I = \frac{1}{2} m r^2\]Substitute the moment of inertia into the angular momentum equation:

\[\frac{1}{2} m r_1^2 \cdot \omega_1 = \frac{1}{2} m r_2^2 \cdot \omega_2\]Since the mass $m$ and the constant $\frac{1}{2}$ cancel out, we get:

\[r_1^2 \cdot \omega_1 = r_2^2 \cdot \omega_2\]Solve for the final rotation speed $\omega_2$:

\[\omega_2 = \frac{r_1^2 \cdot \omega_1}{r_2^2}\] \[\omega_2 = \frac{(1.496 \times 10^{14} \, \text{m})^2 \cdot 1 \times 10^{-3} \, \text{rad/s}}{(1.496 \times 10^{13} \, \text{m})^2}\] \[\omega_2 = \frac{2.238 \times 10^{25} \, \text{m}^2 \cdot \text{rad/s}}{2.238 \times 10^{26} \, \text{m}^2}\] \[\omega_2 = 0.1 \, \text{rad/s}\]Therefore, the final rotation speed of the protostar’s accretion disk is $0.1 \, \text{rad/s}$.

In this example, we examined a thin disc that changed its radius, but did not change its mass. We used our algebra skills to find that the new rotational speed can be calculated with the equation:

\[\omega_2 = \frac{r_1^2 \cdot \omega_1}{r_2^2}\]

which always works for this scenario!! Hopefully this exemplifies why using algebra and variables is much more powerful than just plugging numbers into a calculator :)

Angular Momentum in Star Formation

Formation of Accretion Disks: As the molecular cloud contracts, its rotation speed increases, and the material flattens into an accretion disk around the protostar. This disk is essential for the growth of the protostar, channeling material onto it and setting the stage for planet formation.

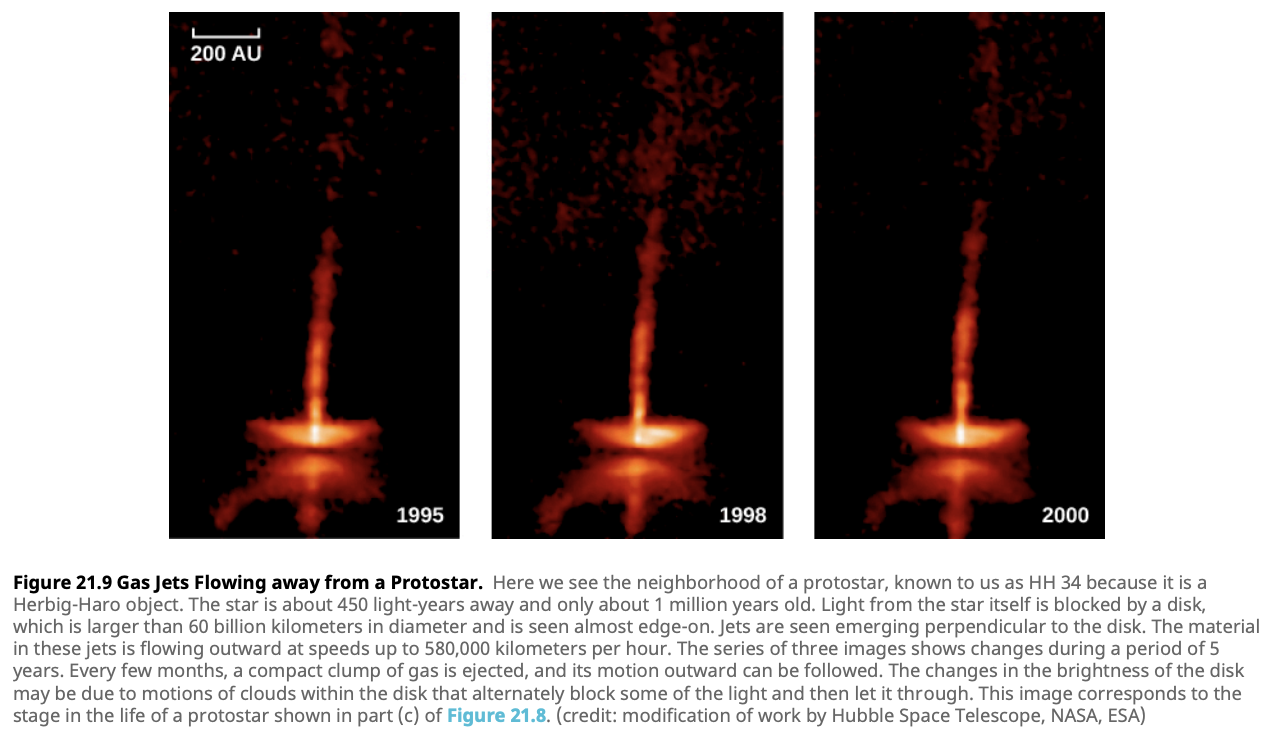

Bipolar Outflows: The rotating disk and the magnetic fields generate jets of gas that are ejected along the poles of the protostar. These jets carry away excess angular momentum, preventing the protostar from spinning too fast and allowing more material to accrete onto the star.

These outflows can be observed as dazzling jets extending far into space, often lighting up surrounding gas clouds and creating stunning visual spectacles known as Herbig-Haro objects. These objects are markers of young, forming stars, providing astronomers with clues about the processes occurring within these hidden stellar nurseries.

By understanding the role of angular momentum in star formation, we can appreciate the delicate balance of forces that shape the birth of stars. From the initial collapse of a molecular cloud to the formation of accretion disks and the ejection of bipolar outflows, each step is a testament to the intricate dance of physics that governs our universe.

Observation and Evidence of Star Formation

Stars are born in regions shrouded by thick clouds of gas and dust, making them invisible to the naked eye. However, by using a variety of sophisticated tools and techniques, astronomers can unveil these stellar nurseries and gather critical evidence of star formation.

Methods of Observing Star Formation

1. Infrared Astronomy: Infrared light is a powerful tool in the astronomer’s toolkit. Unlike visible light, which is easily blocked by dust, infrared light can penetrate these thick clouds, allowing us to see what lies within. By observing in the infrared spectrum, astronomers can detect the faint glow of young stars and protostars still nestled in their natal environments. These infrared observations have revolutionized our understanding of star formation, revealing entire regions of space teeming with stars in various stages of development.

Fun Fact: The Spitzer Space Telescope, an infrared observatory, has provided some of the most detailed images of star-forming regions, revealing the intricate structures within molecular clouds.

2. Radio Telescopes: Radio telescopes offer another window into the hidden process of star formation. These telescopes are designed to detect the faint radio waves emitted by molecules in cold, dense regions of space. One of the most important molecules detected in these regions is carbon monoxide (CO). By mapping the distribution of CO and other molecules, astronomers can identify the locations of molecular clouds, where star formation is actively occurring. Radio observations can also reveal the movement of gas within these clouds, helping to trace the dynamics of the star formation process.

Did You Know? The Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile is one of the most powerful radio telescopes in the world, capable of capturing detailed images of star-forming regions in distant galaxies.

By combining these observational techniques, astronomers have been able to build a detailed picture of how stars form, even in the most obscured regions of the galaxy. These observations not only confirm theoretical models but also provide new insights that continue to push the boundaries of our understanding of the universe.

Check Your Understanding

-

Gravitational Collapse Trigger: Explain how a supernova shockwave can trigger the gravitational collapse of a molecular cloud and initiate the process of star formation.

-

Angular Momentum: What roles does the conservation of angular momentum play in the various stages of star formation?

-

Infrared Astronomy: Why is infrared light particularly useful for observing star formation? What does it reveal that visible light cannot?

-

Radio Telescopes and Molecular Clouds: Explain how radio telescopes help astronomers detect molecular clouds and understand the star formation process. What specific molecules are often observed?

-

Angular Momentum and Accretion Disks: A collapsing molecular cloud forms an accretion disk around a protostar due to the conservation of angular momentum. If the initial radius of the disk is $500 \, \text{AU}$ with a rotation speed of $0.01 \, \text{rad/s}$, and the disk contracts to $50 \, \text{AU}$, calculate the final rotation speed of the disk.

-

Planet Formation: Describe the process by which planetesimals form within the accretion disk around a young star. How do these planetesimals eventually form planets?

-

Moment of Inertia Calculation: Calculate the moment of inertia for a solid sphere with a mass of $5 \times 10^{30} \, \text{kg}$ and a radius of $7 \times 10^{10} \, \text{m}$.

Resources

- Astronomy (2016). Andrew Fraknoi, David Morrison, and Sidney C. Wolff.

- Foundations of Astrophysics (2010). Barbara Ryden and Bradley M. Peterson.