Introduction

Circular motion is a fundamental concept in astronomy, playing a crucial role in understanding the behavior of celestial bodies. When studying the orbits of planets around the Sun, moons around their planets, and artificial satellites around Earth, we observe that these objects follow curved paths. This motion is not only key to the structure of our solar system but also to the mechanics of many astronomical phenomena. In this lesson, we will delve into the principles of circular motion, examining its effects on the orbits of various celestial objects and the forces that maintain these orbits.

Video

Watch this video to get a visual introduction to the concepts of circular motion. The first half is particularly useful for our discussion; you can ignore the discussion on centrifugal force.

Uniform Circular Motion

Uniform circular motion occurs when an object moves along a circular path at a constant speed. Despite the constant speed, the object’s velocity is continuously changing because its direction is always changing. This constant change in direction results in an acceleration towards the center of the circular path, known as centripetal acceleration.

Characteristics:

- Constant Speed: The magnitude of the velocity remains unchanged.

- Changing Direction: The direction of the velocity vector changes continuously.

- Centripetal Acceleration: The acceleration is directed towards the center of the circular path.

For simple calculations regarding the orbits of planets, moons, satellites, and other celestial bodies, we can approximate these orbits by assuming they are in circular motion. This simplification allows us to use the principles of uniform circular motion to understand and predict their behavior.

Examples in Astronomy:

- Planets orbiting the Sun: The gravitational pull of the Sun provides the necessary centripetal force.

- Moons orbiting planets: Moons remain in orbit due to the gravitational pull of their parent planets.

- Satellites orbiting Earth: Artificial satellites stay in orbit due to the Earth’s gravitational force.

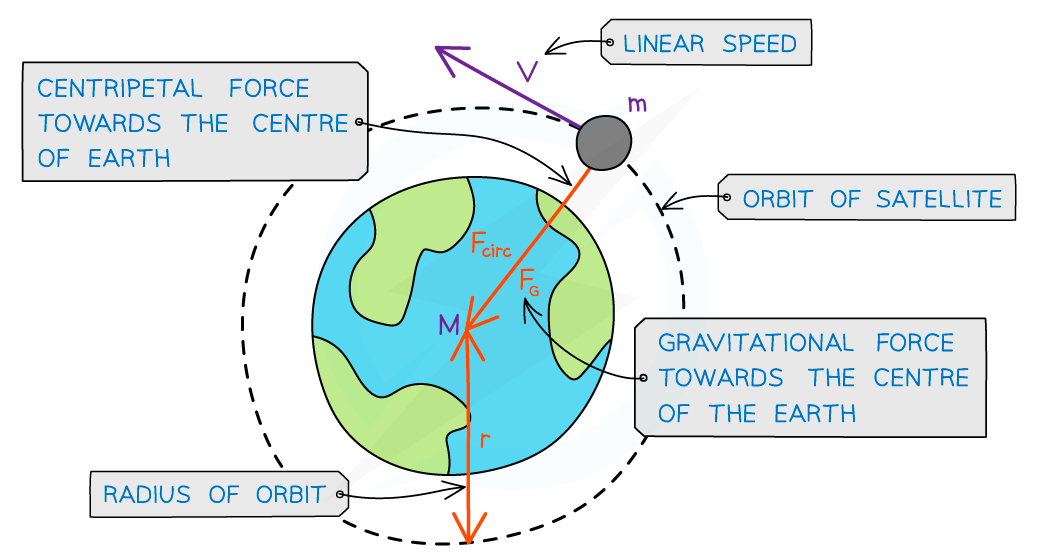

Centripetal Force

Centripetal force is the force required to keep an object moving in a circular path, directed towards the center of the circle. This force is essential because it counters the object’s inertia, which would otherwise cause it to move in a straight line. The word “centripetal” comes from Latin, meaning “center-seeking,” highlighting the force’s direction toward the center of the circular path.

Centripetal force keeps an object moving in a circular path by constantly pulling it towards the center.

In the context of circular motion, any force that keeps an object on its curved path acts as a centripetal force. This could be tension in a string for a ball being swung around, friction between tires and the road for a car turning a corner, or gravity for celestial bodies in orbit.

Mathematical Expression:

\(F_c = \frac{mv^2}{r}\) where:

- $ F_c $ is the centripetal force

- $ m $ is the mass of the object

- $ v $ is the velocity of the object

- $ r $ is the radius of the circular path

Relation to Gravitational Force

In astronomy, the most common centripetal force is gravity. For planetary motion, gravity provides the necessary centripetal force to keep a planet in orbit around the Sun. Similarly, gravity keeps moons orbiting their planets and artificial satellites orbiting the Earth.

In orbital motion, the centripetal force is the force of gravity.

When we look at the gravitational force acting as the centripetal force, the expressions can be equated:

\[F_g = F_c\]

This leads to the equation:

\[\frac{GMm}{r^2} = \frac{mv^2}{r}\]

Here, $ G $ is the gravitational constant and $ M $ is the mass of the central body (such as the Sun or Earth). Simplifying this equation allows us to understand the relationships between the various forces and motions involved in orbital mechanics.

Given:

Mass of Earth, $ m = 5.97 \times 10^{24} \, \text{kg} $

Velocity of Earth, $ v = 29.78 \, \text{km/s} = 2.978 \times 10^4 \, \text{m/s} $

Radius of Earth’s orbit, $ r = 1.496 \times 10^{11} \, \text{m} $

Solution:

\[F_c = \frac{(5.97 \times 10^{24} \, \text{kg})(2.978 \times 10^4 \, \text{m/s})^2}{1.496 \times 10^{11} \, \text{m}}\] \[F_c \approx 3.54 \times 10^{22} \, \text{N}\]

In this example, the immense centripetal force required to keep Earth in its orbit is provided by the gravitational pull of the Sun. This force constantly pulls Earth towards the Sun, balancing the inertia of Earth’s motion, which attempts to move it in a straight line. This delicate balance is what maintains the stable orbit of our planet.

Centripetal Acceleration

Centripetal acceleration is the acceleration experienced by an object moving in a circle at a constant speed, directed towards the center of the circle. This acceleration is what causes the object to change direction continuously.

Formula:

\[a_c = \frac{v^2}{r}\]

Application to Circular Orbits

In circular orbits, the centripetal acceleration is provided by the gravitational force acting on the orbiting body.

Given:

Velocity of Earth, $ v = 29.78 \, \text{km/s} = 2.978 \times 10^4 \, \text{m/s} $

Radius of Earth’s orbit, $ r = 1.496 \times 10^{11} \, \text{m} $

Solution:

\[a_c = \frac{(2.978 \times 10^4 \, \text{m/s})^2}{1.496 \times 10^{11} \, \text{m}}\] \[a_c \approx 5.93 \times 10^{-3} \, \text{m/s}^2\]

Gravity and Circular Motion Simulator

Feel free to play around with the simulator below to get a feel for how gravity impacts orbits of planets, moons, and satellites!

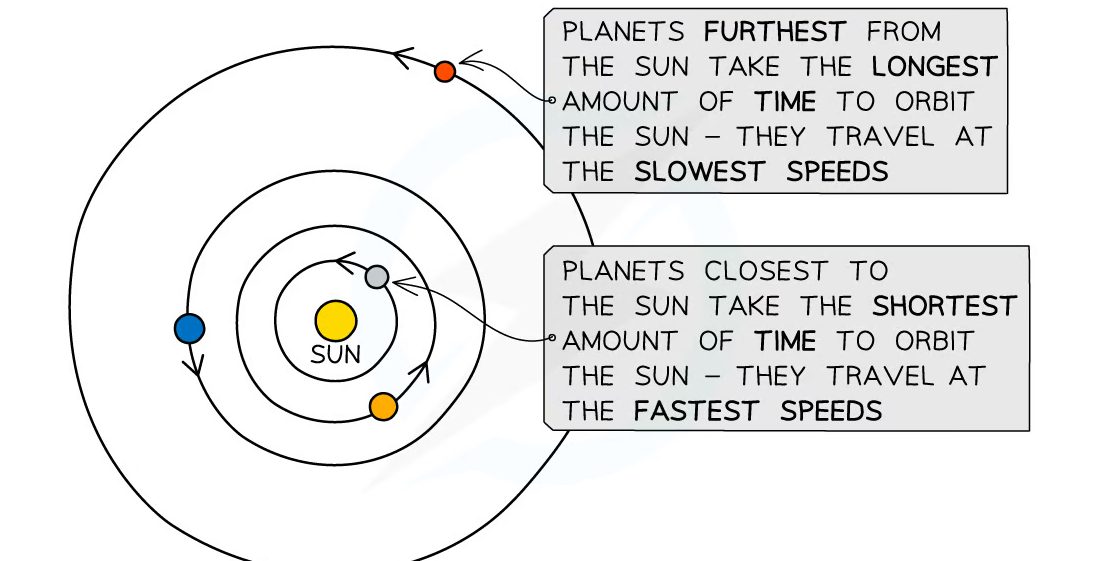

Orbital Speed

Understanding the speed at which an object orbits a celestial body is crucial in astronomy. The orbital speed determines how long it takes for an object, such as a planet, moon, or satellite, to complete one full orbit around its primary body.

By combining Newton’s law of universal gravitation with the concept of centripetal force, we can derive the formula for orbital speed. This derivation provides insight into how gravitational forces and the mass of celestial bodies influence the motion of orbiting objects.

Derivation of Orbital Speed

To derive the orbital speed, we start with the fact that the gravitational force ($F_g$) acting on an object in orbit provides the necessary centripetal force ($F_c$) to keep it in circular motion.

Step-by-Step Derivation:

- Equate Gravitational Force to Centripetal Force:

\[F_g = F_c\]

- Express Gravitational Force:

\[F_g = \frac{GMm}{r^2}\]

- Where $G$ is the gravitational constant, $M$ is the mass of the central body, $m$ is the mass of the orbiting object, and $r$ is the radius of the orbit.

- Express Centripetal Force:

\[F_c = \frac{mv^2}{r}\]

- Where $v$ is the orbital speed.

- Set the Expressions Equal to Each Other:

\[\frac{GMm}{r^2} = \frac{mv^2}{r}\]

- Simplify the Equation:

- Cancel $m$ from both sides:

\[\frac{GM}{r^2} = \frac{v^2}{r}\]

- Multiply both sides by $r$:

\[\frac{GM}{r} = v^2\]

- Cancel $m$ from both sides:

- Solve for Orbital Speed ($v$):

\[v = \sqrt{\frac{GM}{r}}\]

This formula shows that the orbital speed of an object depends on the gravitational constant ($G$), the mass of the central body ($M$), and the radius of the orbit ($r$).

Importance of Orbital Speed in Astronomy

Understanding orbital speed is essential for:

- Predicting Orbital Periods: The time it takes for an object to complete one orbit.

- Satellite Deployment: Ensuring satellites remain in stable orbits.

- Planetary Motion: Studying the dynamics of planets and their moons.

- Space Missions: Planning trajectories for space probes and missions.

Orbital speed helps astronomers and scientists comprehend the delicate balance of forces that keep celestial bodies in motion and ensures the stability of their orbits.

By mastering the concept of orbital speed, we can better appreciate the intricate dance of planets, moons, and satellites in our universe.

Given:

Mass of Earth, $ M = 5.97 \times 10^{24} \, \text{kg} $

Radius of Earth, $ R = 6.371 \times 10^6 \, \text{m} $

Height above the surface, $ h = 300 \times 10^3 \, \text{m} $

Gravitational constant, $ G = 6.674 \times 10^{-11} \, \text{N m}^2/\text{kg}^2 $

Solution:

\[r = R + h = 6.371 \times 10^6 \, \text{m} + 300 \times 10^3 \, \text{m} = 6.671 \times 10^6 \, \text{m}\] \[v = \sqrt{\frac{6.674 \times 10^{-11} \, \text{N m}^2/\text{kg}^2 \times 5.97 \times 10^{24} \, \text{kg}}{6.671 \times 10^6 \, \text{m}}}\] \[v \approx 7.73 \times 10^3 \, \text{m/s} = 7.73 \, \text{km/s}\]

Check Your Understanding

- Calculate the centripetal force acting on a 1000 kg satellite orbiting the Earth at a height of 500 km above the surface.

Hint: The height above the surface is not the entire radius of the orbit).

- Given a satellite orbiting Earth at a height where the radius of the orbit is 7,000 km, calculate the orbital speed of the satellite. Assume Earth’s mass is $5.97 \times 10^{24} \, \text{kg}$ and the gravitational constant $G$ is $6.674 \times 10^{-11} \, \text{N m}^2/\text{kg}^2$.

- Describe the relationship between the radius of an orbit and the orbital speed of a satellite. What happens to the speed if the radius increases?

- A moon orbits a planet at a radius of $3.84 \times 10^8 \, \text{m}$ with an orbital speed of $1.02 \times 10^3 \, \text{m/s}$. Calculate the mass of the planet.

- Calculate the centripetal acceleration of the Earth in its orbit around the Sun. Use the given values: velocity of Earth $v = 29.78 \, \text{km/s}$ and radius of Earth’s orbit $r = 1.496 \times 10^{11} \, \text{m}$.

- Explain why satellites need to be launched at a specific speed to remain in stable orbit around the Earth. What would happen if the speed were too low or too high?

- A satellite completes one full orbit around Earth in 90 minutes. If the radius of the orbit is $7.0 \times 10^6 \, \text{m}$, calculate the orbital speed of the satellite.

Hint: Use the formula for the circumference of a circle, $C = 2 \pi r$, to find the distance traveled in one orbit.

Resources

- Astronomy (2016). Andrew Fraknoi, David Morrison, and Sidney C. Wolff.

- An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics (2017). Bradley W. Carroll and Dale A. Ostlie.