Imagine a quiet afternoon in the English countryside, where a young scholar named Isaac Newton sits pondering under an apple tree. Suddenly, an apple breaks free from its branch and tumbles to the ground. This seemingly mundane event sparks a revelation in Newton’s mind—a revelation that would transform our understanding of the universe. What if the same force that pulled the apple to the earth also governed the motion of the moon and the planets? This epiphany led Newton to formulate the law of universal gravitation, a groundbreaking theory that connects the motions of celestial bodies to the everyday experiences of objects falling to the ground.

Video

Watch this video for an explanation of Newton's law of universal gravitation.

Historical Context

At the age of 23, while the Great Plague of London raged and Cambridge University was shut down, Newton retreated to his family home. It was during this period, known as his “Annus Mirabilis” or “Year of Wonders,” that Newton made groundbreaking discoveries. He formulated the principles that would later be published in his seminal work, “Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica” in 1687. This book laid the foundation for classical mechanics and introduced the world to Newton’s three laws of motion.

Did You Know?

Newton’s productive isolation led to the development of his laws of motion and universal gravitation, demonstrating that even in the darkest times, human ingenuity can shine brightly.

Newton’s Laws of Motion

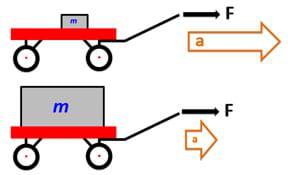

Newton’s laws of motion describe the relationship between a body and the forces acting upon it. Among these, his second law is fundamental to understanding motion:

Newton’s Second Law:

$F = ma$

This law states that the force acting on an object is equal to the mass of that object multiplied by its acceleration. It provides a quantitative description of the motion of objects and is essential for understanding how forces affect motion.

But what does acceleration actually mean? Acceleration is a change in the velocity of an object over time. This could be a change in the object’s speed, its direction of motion, or both. When a force is applied to an object, it causes the object to accelerate in the direction of the force. The amount of acceleration depends on the mass of the object and the magnitude of the force.

Implications of Newton’s Second Law:

Direct Proportionality to Force: If you apply a greater force to an object, it will accelerate more. For example, if you push a shopping cart, the harder you push, the faster it accelerates.

Inverse Proportionality to Mass: If the object has more mass, it will accelerate less for the same amount of force. This is why a heavy truck accelerates more slowly than a small car when the same force is applied.

Examples to Illustrate Newton’s Second Law:

-

Launching a Satellite into Orbit

Example: A rocket is being used to launch a 2,000 kg satellite into orbit. If the rocket engines provide a constant thrust of 50,000 N, calculate the acceleration of the satellite.Given:

Mass of satellite, $ m = 2000 \, \text{kg} $

Thrust (force) provided by rocket engines, $ F = 50,000 \, \text{N} $

Solution:

Using Newton’s second law, $ F = ma $, we can solve for acceleration, $ a $:

\[a = \frac{F}{m}\] \[a = \frac{50,000 \, \text{N}}{2000 \, \text{kg}}\] \[a = 25 \, \text{m/s}^2\]

Therefore, the acceleration of the satellite is $ 25 \, \text{m/s}^2 $.

This means that every second, the satellite’s speed increases by 25 meters per second, as long as the force is applied.

-

Calculating the Force on an Astronaut in Space

Example: An astronaut with a mass of 90 kg is floating in space. During a spacewalk, the astronaut uses a jetpack to apply a force of 180 N. Calculate the acceleration experienced by the astronaut.Given:

Mass of astronaut, $ m = 90 \, \text{kg} $

Force applied by jetpack, $ F = 180 \, \text{N} $

Solution:

Using Newton’s second law, $ F = ma $, we can solve for acceleration, $ a $:

\[a = \frac{F}{m}\] \[a = \frac{180 \, \text{N}}{90 \, \text{kg}}\] \[a = 2 \, \text{m/s}^2\]

Therefore, the acceleration experienced by the astronaut is $ 2 \, \text{m/s}^2 $.

This means that every second, the astronaut’s speed increases by 2 meters per second in the direction of the force applied by the jetpack.

Understanding acceleration is crucial for comprehending how objects move in response to forces. It explains why astronauts float in space (lack of a significant external force acting on them) and how spacecraft maneuver in the vacuum of space. Newton’s second law provides the foundation for analyzing and predicting these motions, making it a cornerstone of physics and engineering.

Development of Gravitational Theory

Before Newton’s insights, the understanding of motion and planetary orbits was fragmented. Galileo Galilei had shown through his experiments that objects fall at the same rate regardless of their mass. Meanwhile, Johannes Kepler had formulated his laws of planetary motion, describing how planets orbit the sun in elliptical paths. But it was Newton who synthesized these ideas into a unified theory of gravitation.

The Universal Force of Gravity

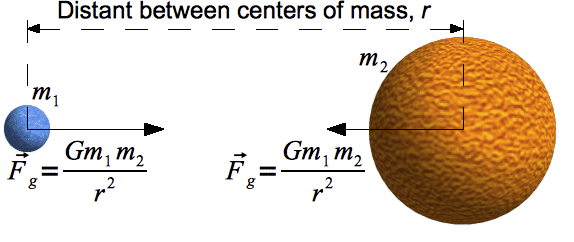

Newton realized that the force causing an apple to fall from a tree is the same force that governs the motion of the moon and planets. This universal force, which he called gravity, acts on all objects with mass. He articulated this in his law of universal gravitation:

Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation:

\[F = G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}\]

where:

- $ F $ is the gravitational force,

- $ G $ is the gravitational constant ($6.67430 \times 10^{-11} \, \text{m}^3 \text{kg}^{-1} \text{s}^{-2}$),

- $ m_1 $ and $ m_2 $ are the masses of the two objects,

- $ r $ is the distance between the centers of the two masses.

| Quantity | Unit | Description |

|---|---|---|

| $ F $ | Newtons (N) | Gravitational force |

| $ m_1, m_2 $ | Kilograms (kg) | Masses of the objects |

| $ r $ | Meters (m) | Distance between the centers of the masses |

| $ G $ | $ \text{m}^3 \text{kg}^{-1} \text{s}^{-2} $ | Gravitational constant |

This formula expresses that the gravitational force ($F$) between two masses ($m_1$ and $m_2$) is directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance ($r$) between their centers. Here, $G$ is the gravitational constant, a value that makes this equation work universally.

Inverse Square Law

Newton’s law of universal gravitation states that the gravitational force between two masses is inversely proportional to the square of the distance between their centers.

This equation reveals that as the distance between two objects increases, the gravitational force between them decreases rapidly. Specifically, if the distance is doubled, the gravitational force becomes one-fourth as strong; if the distance is tripled, the force is reduced to one-ninth, and so on. This inverse square relationship is a fundamental concept in physics.

Recall:

You have encountered an inverse square relationship before when learning about the flux from a star. The flux, or the apparent brightness of a star as seen from Earth, decreases with the square of the distance from the star. Just as with gravitational force, if you move twice as far from a star, the flux you observe becomes one-fourth as bright. This similarity can help you intuitively understand how gravity behaves over distance.

Gravitational Constant (G)

The gravitational constant $ G $ is a key quantity in Newton’s law of universal gravitation. It represents the strength of gravity and its value is approximately $ 6.67430 \times 10^{-11} \, \text{m}^3 \text{kg}^{-1} \text{s}^{-2} $.

The value of $G= 6.67430 \times 10^{-11} \, \text{m}^3 \text{kg}^{-1} \text{s}^{-2} $ is determined experimentally and remains constant across the universe.

Given:

Mass of Earth, $ m_1 = 5.972 \times 10^{24} \, \text{kg} $

Mass of the Moon, $ m_2 = 7.348 \times 10^{22} \, \text{kg} $

Distance between Earth and Moon, $ r = 384,400 \, \text{km} = 384,400,000 \, \text{m} $

Gravitational constant, $ G = 6.67430 \times 10^{-11} \, \text{m}^3 \text{kg}^{-1} \text{s}^{-2} $

Using Newton’s universal law of gravitation:

\[F = G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2}\] \[F = 6.67430 \times 10^{-11} \, \frac{(5.972 \times 10^{24} \, \text{kg}) (7.348 \times 10^{22} \, \text{kg})}{(384,400,000 \, \text{m})^2}\] \[F \approx 1.982 \times 10^{20} \, \text{N}\]Therefore, the gravitational force between Earth and the Moon is approximately $ 1.982 \times 10^{20} \, \text{N} $.

This immense force keeps the Moon in orbit around Earth, demonstrating the power of gravitational attraction even over vast distances.

Applications and Implications

Gravity on Earth

Imagine standing on a scale to measure your weight. What you’re actually measuring is the gravitational force that Earth exerts on you. This force, which keeps your feet firmly planted on the ground, is a manifestation of gravity. Newton’s second law, $F = ma$, helps us calculate this force. On Earth, the acceleration due to gravity, $g$, is approximately $9.8 \, \text{m/s}^2$. Therefore, your weight can be calculated using the equation:

\[F = mg\]

For example, let’s calculate the weight of a 70 kg person on Earth:

\[F = 70 \, \text{kg} \times 9.8 \, \text{m/s}^2 = 686 \, \text{N}\]

This calculation shows that the gravitational force acting on a 70 kg person is 686 newtons. This force is what we commonly refer to as “weight.”

Orbital Motion

Now, let’s take a journey beyond Earth, into the vast expanse of space. Here, gravity plays a crucial role in orchestrating the cosmic dance of planets and moons. The same force that keeps us grounded also keeps planets in orbit around the Sun and moons around their respective planets.

Imagine Earth orbiting the Sun. Despite the immense distance between them, the Sun’s gravitational pull provides the centripetal force necessary to keep Earth in its nearly circular orbit. This delicate balance of forces ensures that Earth doesn’t spiral into the Sun or drift away into the cold void of space.

This gravitational pull isn’t limited to planets and stars. It also governs the motion of artificial satellites orbiting Earth. Engineers and scientists must carefully calculate the gravitational forces to ensure these satellites maintain their intended orbits, allowing us to enjoy modern conveniences like GPS and satellite television.

Tides

Let’s shift our gaze back to Earth and focus on the rhythmic rise and fall of ocean tides. This mesmerizing phenomenon is a direct result of the gravitational interactions between Earth, the Moon, and the Sun.

As the Moon orbits Earth, its gravitational pull tugs at the planet’s oceans, creating bulges of water known as high tides. On the side of Earth facing the Moon, the gravitational pull is strongest, causing the water to be pulled towards the Moon. Simultaneously, on the opposite side of Earth, inertia creates another bulge. These opposing bulges result in two high tides each day.

The Sun, though much farther away, also influences the tides. During full and new moons, the gravitational forces of the Moon and Sun align, producing exceptionally high and low tides known as spring tides. Conversely, during quarter moons, when the gravitational forces of the Moon and Sun are perpendicular to each other, we experience neap tides, which are less extreme.

Did You Know?

The interplay of gravitational forces between Earth, the Moon, and the Sun not only creates tides but also plays a crucial role in the Earth’s rotational dynamics. This gravitational dance subtly influences the length of our days over long periods.

Check Your Understanding

- Calculate the gravitational force between Earth (mass $ 5.972 \times 10^{24} \, \text{kg} $) and a 70 kg person standing on its surface (distance from the center of Earth is approximately 6,371,000 m).

- How does the force of gravity in the International Space Station (orbiting an average of 400 km above Earth’s surface) compare with that

on the ground?

- Two asteroids begin to gravitationally attract one another. If one asteroid has twice the mass of the other, which one experiences the greater force? Which one experiences the greater acceleration?

- If there is gravity where the International Space Station (ISS) is located above Earth, why doesn’t the space station get pulled back down to Earth?

- If identical spacecraft were orbiting Mars and Earth at identical radii (distances), which spacecraft would be moving faster? Why?

- Suppose astronomers find an earthlike planet that is twice the size of Earth (that is, its radius is twice that of Earth’s). What must be the mass of this planet such that the gravitational force (Fgravity) at the surface would be identical to Earth’s?

Resources

- Astronomy (2016). Andrew Fraknoi, David Morrison, and Sidney C. Wolff.

- An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics (2017). Bradley W. Carroll and Dale A. Ostlie.

- RESOURCE GK-12 Program. College of Engineering, University of California Davis.